Introduction to outbreak analytics

Last updated on 2025-03-18 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 12 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How to calculate delays from line list data?

- How to fit a probability distribution to delay data?

- Why it is important to account for delays in outbreak analytics?

Objectives

- Use the pipe operator

%>%to structure sequences of data operations. - Count observations in each group using

count()function. - Pivot data from wide-to-long or long-to-wide using family of

pivot_*()functions. - Create new columns from existing columns using

mutate()function. - Keep or drop columns by their names using

select(). - Keep rows that match a condition using

filter(). - Extract a single column using

pull(). - Create graphics declaratively using ggplot2.

Prerequisite

Setup an RStudio project and folder

- Create an RStudio project. If needed, follow this how-to guide on “Hello RStudio Projects” to create one.

- Inside the RStudio project, create the

data/folder. - Inside the

data/folder, save the linelist.csv file.

Checklist

RStudio projects

The directory of an RStudio Project named, for example

training, should look like this:

training/

|__ data/

|__ training.RprojRStudio Projects allows you to use relative

file paths with respect to the R Project, making your

code more portable and less error-prone. Avoids using

setwd() with absolute paths like

"C:/Users/MyName/WeirdPath/training/data/file.csv".

Challenge

Let’s starts by creating New Quarto Document!

- In the RStudio IDE, go to: File > New File > Quarto Document

- Accept the default options

- Save the file with the name

01-report.qmd - Use the

Renderbutton to render the file and preview the output.

Introduction

A new Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak has been notified in a country in West Africa. The Ministry of Health is coordinating the outbreak response and has contracted you as a consultant in epidemic analysis to inform the response in real-time. The available report of cases is coming from hospital admissions.

Let’s start by loading the package readr to read

.csv data, dplyr to manipulate data,

tidyr to rearrange it, and here to write

file paths within your RStudio project. We’ll use the pipe

%>% to connect some of their functions, including others

from the package ggplot2, so let’s call to the package

tidyverse that loads them all:

R

# Load packages

library(tidyverse) # loads readr, dplyr, tidyr and ggplot2

OUTPUT

── Attaching core tidyverse packages ──────────────────────── tidyverse 2.0.0 ──

✔ dplyr 1.1.4 ✔ readr 2.1.5

✔ forcats 1.0.0 ✔ stringr 1.5.1

✔ ggplot2 3.5.1 ✔ tibble 3.2.1

✔ lubridate 1.9.4 ✔ tidyr 1.3.1

✔ purrr 1.0.4

── Conflicts ────────────────────────────────────────── tidyverse_conflicts() ──

✖ dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

✖ dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

ℹ Use the conflicted package (<http://conflicted.r-lib.org/>) to force all conflicts to become errorsChecklist

The double-colon

The double-colon :: in R let you call a specific

function from a package without loading the entire package into the

current environment.

For example, dplyr::filter(data, condition) uses

filter() from the dplyr package.

This helps us remember package functions and avoid namespace conflicts.

Explore data

For the purpose of this episode, we will read a pre-cleaned line list data. Following episodes will tackle how to solve cleaning tasks.

R

# Read data

# e.g.: if path to file is data/linelist.csv then:

cases <- readr::read_csv(

here::here("data", "linelist.csv")

)

Checklist

Why should we use the {here} package?

The package here simplifies file referencing in R projects. It allows them to work across different operating systems (Windows, Mac, Linux). This feature, called cross-environment compatibility, eliminates the need to adjust file paths. For example:

- On Windows, paths are written using backslashes (

\) as the separator between folder names:"data\raw-data\file.csv" - On Unix based operating system such as macOS or Linux the forward

slash (

/) is used as the path separator:"data/raw-data/file.csv"

The here package adds one more layer of reproducibility to your work. For more, read this tutorial about open, sustainable, and reproducible epidemic analysis with R

R

# Print line list data

cases

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 166 × 11

case_id generation date_of_infection date_of_onset date_of_hospitalisation

<chr> <dbl> <date> <date> <date>

1 d1fafd 0 NA 2014-04-07 2014-04-17

2 53371b 1 2014-04-09 2014-04-15 2014-04-20

3 f5c3d8 1 2014-04-18 2014-04-21 2014-04-25

4 e66fa4 2 NA 2014-04-21 2014-05-06

5 49731d 0 2014-03-19 2014-04-25 2014-05-02

6 0f58c4 2 2014-04-22 2014-04-26 2014-04-29

7 6c286a 2 NA 2014-04-27 2014-04-27

8 881bd4 3 2014-04-26 2014-05-01 2014-05-05

9 d58402 2 2014-04-23 2014-05-01 2014-05-10

10 f9149b 3 NA 2014-05-03 2014-05-04

# ℹ 156 more rows

# ℹ 6 more variables: date_of_outcome <date>, outcome <chr>, gender <chr>,

# hospital <chr>, lon <dbl>, lat <dbl>Discussion

Take a moment to review the data and its structure..

- Do the data and format resemble line lists you’ve encountered before?

- If you were part of the outbreak investigation team, what additional information might you want to collect?

The information to collect will depend on the questions we need to give a response.

At the beginning of an outbreak, we need data to give a response to questions like:

- How fast does an epidemic grow?

- What is the risk of death?

- How many cases can I expect in the coming days?

Informative indicators are:

- growth rate, reproduction number.

- case fatality risk, hospitalization fatality risk.

- projection or forecast of cases.

Useful data are:

- date of onset, date of death.

- delays from infection to onset, from onset to death.

- percentage of observations detected by surveillance system.

- subject characteristics to stratify the analysis by person, place, time.

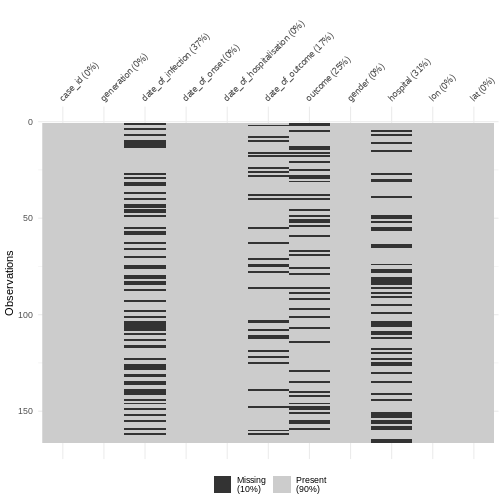

You may notice that there are missing entries.

We can also explore missing data with summary a visualization:

R

cases %>%

visdat::vis_miss()

Discussion

Why do we have more missings on date of infection or date of outcome?

- date of infection: mostly unknown, depended on limited coverage of contact tracing or outbreak research, and sensitive to recall bias from subjects.

- date of outcome: reporting delay

Calculate severity

A frequent indicator for measuring severity is the case fatality risk (CFR).

CFR is defined as the conditional probability of death given confirmed diagnosis, calculated as the cumulative number of deaths from an infectious disease over the number of confirmed diagnosed cases.

We can use the function dplyr::count() to count the

observations in each group of the variable outcome:

R

cases %>%

dplyr::count(outcome)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 3 × 2

outcome n

<chr> <int>

1 Death 65

2 Recover 59

3 <NA> 42Discussion

Report:

What to do with cases whose outcome is

<NA>?Should we consider missing outcomes to calculate the CFR?

Keeping cases with missing outcome is useful to track the incidence of number of new cases, useful to assess transmission.

However, when assessing severity, CFR estimation is sensitive to:

Right-censoring bias. If we include observations with unknown final status we can underestimate the true CFR.

Selection bias. At the beginning of an outbreak, given that health systems collect most clinically severe cases, an early estimate of the CFR can overestimate the true CFR.

To calculate the CFR we can add more functions using the pipe

%>% and structure sequences of data operations

left-to-right.

From the cases object we will use:

-

dplyr::count()to count the observations in each group of the variableoutcome, -

tidyr::pivot_wider()to pivot the data long-to-wide with names fromoutcomeand values fromncolumns, -

cleanepi::standardize_column_names()to standardize column names, -

dplyr::mutate()to create one new columncases_known_outcomeas a function of existing variablesdeathandrecover.

R

# calculate the number of cases with known outcome

cases %>%

dplyr::count(outcome) %>%

tidyr::pivot_wider(names_from = outcome, values_from = n) %>%

cleanepi::standardize_column_names() %>%

dplyr::mutate(cases_known_outcome = death + recover)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 1 × 4

death recover na cases_known_outcome

<int> <int> <int> <int>

1 65 59 42 124This way of writing almost look like writing a recipe!

Challenge

Calculate the CFR as the division of the number of

deaths among known outcomes. Do this

by adding one more pipe %>% in the last code chunk.

Report:

- What is the value of the CFR?

You can use the column names of variables to create one more column:

R

# calculate the naive CFR

cases %>%

count(outcome) %>%

pivot_wider(names_from = outcome, values_from = n) %>%

cleanepi::standardize_column_names() %>%

mutate(cases_known_outcome = death + recover) %>%

mutate(cfr = ... / ...) # replace the ... spaces

R

# calculate the naive CFR

cases %>%

dplyr::count(outcome) %>%

tidyr::pivot_wider(names_from = outcome, values_from = n) %>%

cleanepi::standardize_column_names() %>%

dplyr::mutate(cases_known_outcome = death + recover) %>%

dplyr::mutate(cfr = death / cases_known_outcome)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 1 × 5

death recover na cases_known_outcome cfr

<int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl>

1 65 59 42 124 0.524This calculation is naive because it tends to yield a biased and mostly underestimated CFR due to the time-delay from onset to death, only stabilising at the later stages of the outbreak.

Now, as a comparison, how much a CFR estimate changes if we include unknown outcomes in the denominator?

R

# underestimate the naive CFR

cases %>%

dplyr::count(outcome) %>%

tidyr::pivot_wider(names_from = outcome, values_from = n) %>%

cleanepi::standardize_column_names() %>%

dplyr::mutate(cfr = death / (death + recover + na))

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 1 × 4

death recover na cfr

<int> <int> <int> <dbl>

1 65 59 42 0.392Due to right-censoring bias, if we include observations with unknown final status we can underestimate the true CFR.

Data of today will not include outcomes from patients that are still hospitalised. Then, one relevant question to ask is: In average, how much time it would take to know the outcomes of hospitalised cases? For this we can calculate delays!

Calculate delays

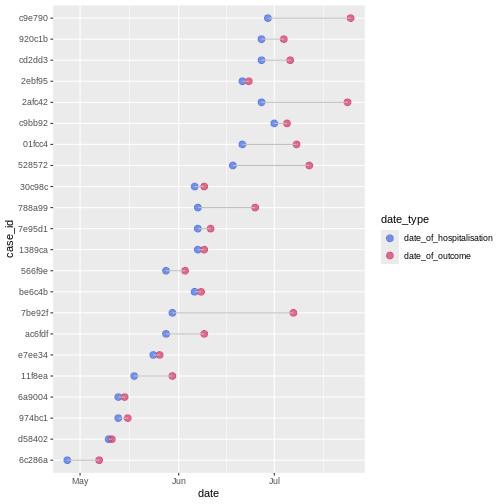

The time between sequence of dated events can vary between subjects. For example, we would expect the date of infection to always be before the date of symptom onset, and the later always before the date of hospitalization.

In a random sample of 30 observations from the cases

data frame we observe variability between the date of hospitalization

and date of outcome:

We can calculate the average time from hospitalisation to outcome from the line list.

From the cases object we will use:

-

dplyr::select()to keep columns using their names, -

dplyr::mutate()to create one new columnoutcome_delayas a function of existing variablesdate_of_outcomeanddate_of_hospitalisation, -

dplyr::filter()to keep the rows that match a condition likeoutcome_delay > 0, -

skimr::skim()to get useful summary statistics

R

# delay from report to outcome

cases %>%

dplyr::select(case_id, date_of_hospitalisation, date_of_outcome) %>%

dplyr::mutate(outcome_delay = date_of_outcome - date_of_hospitalisation) %>%

dplyr::filter(outcome_delay > 0) %>%

skimr::skim(outcome_delay)

| Name | Piped data |

| Number of rows | 123 |

| Number of columns | 4 |

| _______________________ | |

| Column type frequency: | |

| difftime | 1 |

| ________________________ | |

| Group variables | None |

Variable type: difftime

| skim_variable | n_missing | complete_rate | min | max | median | n_unique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| outcome_delay | 0 | 1 | 1 days | 55 days | 7 days | 29 |

Callout

Inconsistencies among sequence of dated-events?

Wait! Is it consistent to have negative time delays from primary to secondary observations, i.e., from hospitalisation to death?

In the next episode called Clean data we will learn how to check sequence of dated-events and other frequent and challenging inconsistencies!

Challenge

To calculate a delay-adjusted CFR, we need to assume a known delay from onset to death.

Using the cases object:

- Calculate the summary statistics of the delay from onset to death.

Keep the rows that match a condition like

outcome == "Death":

R

# delay from onset to death

cases %>%

dplyr::filter(outcome == "Death") %>%

...() # replace ... with downstream code

Is it consistent to have negative delays from onset of symptoms to death?

R

# delay from onset to death

cases %>%

dplyr::select(case_id, date_of_onset, date_of_outcome, outcome) %>%

dplyr::filter(outcome == "Death") %>%

dplyr::mutate(delay_onset_death = date_of_outcome - date_of_onset) %>%

dplyr::filter(delay_onset_death > 0) %>%

skimr::skim(delay_onset_death)

| Name | Piped data |

| Number of rows | 46 |

| Number of columns | 5 |

| _______________________ | |

| Column type frequency: | |

| difftime | 1 |

| ________________________ | |

| Group variables | None |

Variable type: difftime

| skim_variable | n_missing | complete_rate | min | max | median | n_unique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| delay_onset_death | 0 | 1 | 2 days | 17 days | 7 days | 15 |

Where is the source of the inconsistency? Let’s say you want to keep the rows with negative delay values to investigate them. How would you do it?

We can use dplyr::filter() again to identify the

inconsistent observations:

R

# keep negative delays

cases %>%

dplyr::select(case_id, date_of_onset, date_of_outcome, outcome) %>%

dplyr::filter(outcome == "Death") %>%

dplyr::mutate(delay_onset_death = date_of_outcome - date_of_onset) %>%

dplyr::filter(delay_onset_death < 0)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 6 × 5

case_id date_of_onset date_of_outcome outcome delay_onset_death

<chr> <date> <date> <chr> <drtn>

1 c43190 2014-05-06 2014-04-26 Death -10 days

2 bd8c0e 2014-05-17 2014-05-09 Death -8 days

3 49d786 2014-05-20 2014-05-11 Death -9 days

4 e85785 2014-06-03 2014-06-02 Death -1 days

5 60f0c2 2014-06-07 2014-05-30 Death -8 days

6 a48f5d 2014-06-15 2014-06-10 Death -5 days More on estimating a delay-adjusted CFR on the episode about Estimating outbreak severity!

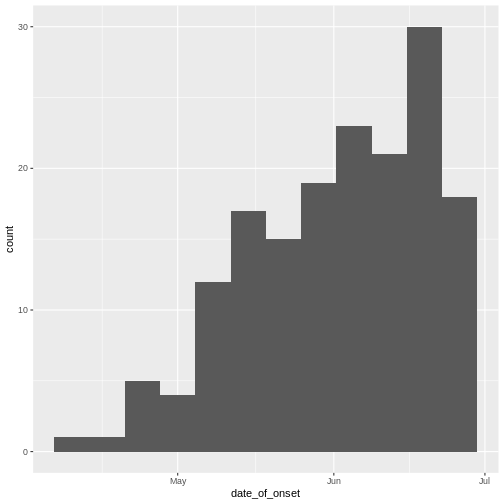

Epidemic curve

The first question we want to know is simply: how bad is it? The first step of the analysis is descriptive. We want to draw an epidemic curve or epicurve. This visualises the incidence over time by date of symptom onset.

From the cases object we will use:

-

ggplot()to declare the input data frame, -

aes()for the variabledate_of_onsetto map togeoms, -

geom_histogram()to visualise the distribution of a single continuous variable with abinwidthequal to 7 days.

R

# incidence curve

cases %>%

ggplot(aes(x = date_of_onset)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 7)

Discussion

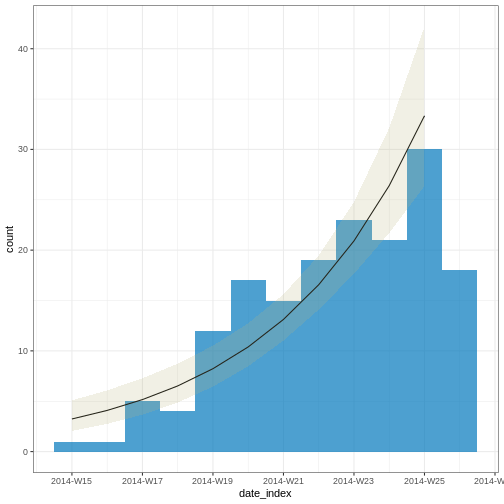

The early phase of an outbreak usually growths exponentially.

- Why exponential growth may not be observed in the most recent weeks?

Close inspection of the line list shows that the last date of any entry (by date of hospitalization) is a bit later than the last date of symptom onset.

From the cases object we can use:

-

dplyr::summarise()to summarise each group down to one row, -

base::maxto calculate the maximum dates of onset and hospitalisation.

When showcasing this to learners in a live coding session, you can

also use cases %>% view() to rearrange by date

columns.

R

cases %>%

dplyr::summarise(

max_onset = max(date_of_onset),

max_hospital = max(date_of_hospitalisation)

)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 1 × 2

max_onset max_hospital

<date> <date>

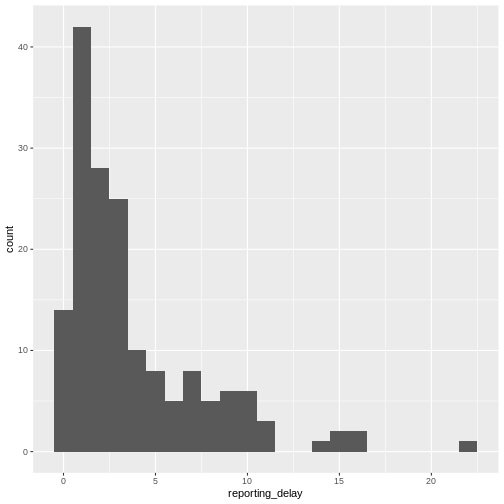

1 2014-06-27 2014-07-07 You may want to examine how long after onset of symptoms cases are hospitalised; this may inform the reporting delay from this line list data:

R

# reporting delay

cases %>%

dplyr::select(case_id, date_of_onset, date_of_hospitalisation) %>%

dplyr::mutate(reporting_delay = date_of_hospitalisation - date_of_onset) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = reporting_delay)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 1)

The distribution of the reporting delay in day units is heavily skewed. Symptomatic cases may take up to two weeks to be reported.

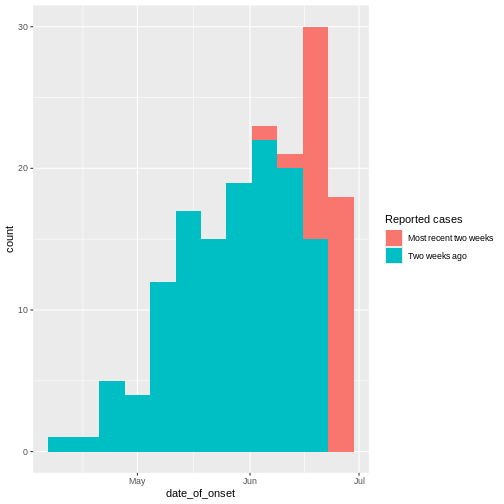

From reports (hospitalisations) in the most recent two weeks, we completed the exponential growth trend of incidence cases within the last four weeks:

Given to reporting delays during this outbreak, it seemed that two weeks ago we had a decay of cases during the last three weeks. We needed to wait a couple of weeks to complete the incidence of cases on each week.

Challenge

Report:

- What indicator can we use to estimate transmission from the incidence curve?

- The growth rate! by fitting a linear model.

- The reproduction number accounting for delays from secondary observations to infection.

More on this topic on episodes about Aggregate and visualize and Quantifying transmission.

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 2 × 6

count_variable term estimate std.error statistic p.value

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 date_of_onset (Intercept) -537. 70.1 -7.67 1.76e-14

2 date_of_onset date_index 0.233 0.0302 7.71 1.29e-14Note: Due to the diagnosed reporting delay, We conveniently truncated the epidemic curve one week before to fit the model! This improves the fitted model to data when quantifying the growth rate during the exponential phase.

Lastly, in order to account for these epidemiological delays when estimating indicators of severity or transmission, in our analysis we need to input delays as Probability Distributions!

Fit a probability distribution to delays

Assess learners based on video refreshers on distributions, likelihood, and maximum likelihood from setup instructions.

We fit a probability distribution to data (like delays) to make inferences about it. These inferences can be useful for Public health interventions and decision making. For example:

From the incubation period distribution we can inform the length of active monitoring or quarantine. We can infer the time by which 99% of infected individuals are expected to show symptoms (Lauer et al., 2020).

From the serial interval distribution we can optimize contact tracing. We can evaluate the need to expand the number of days pre-onset to consider in the contact tracing to include more backwards contacts (Claire Blackmore, 2021; Davis et al., 2020).

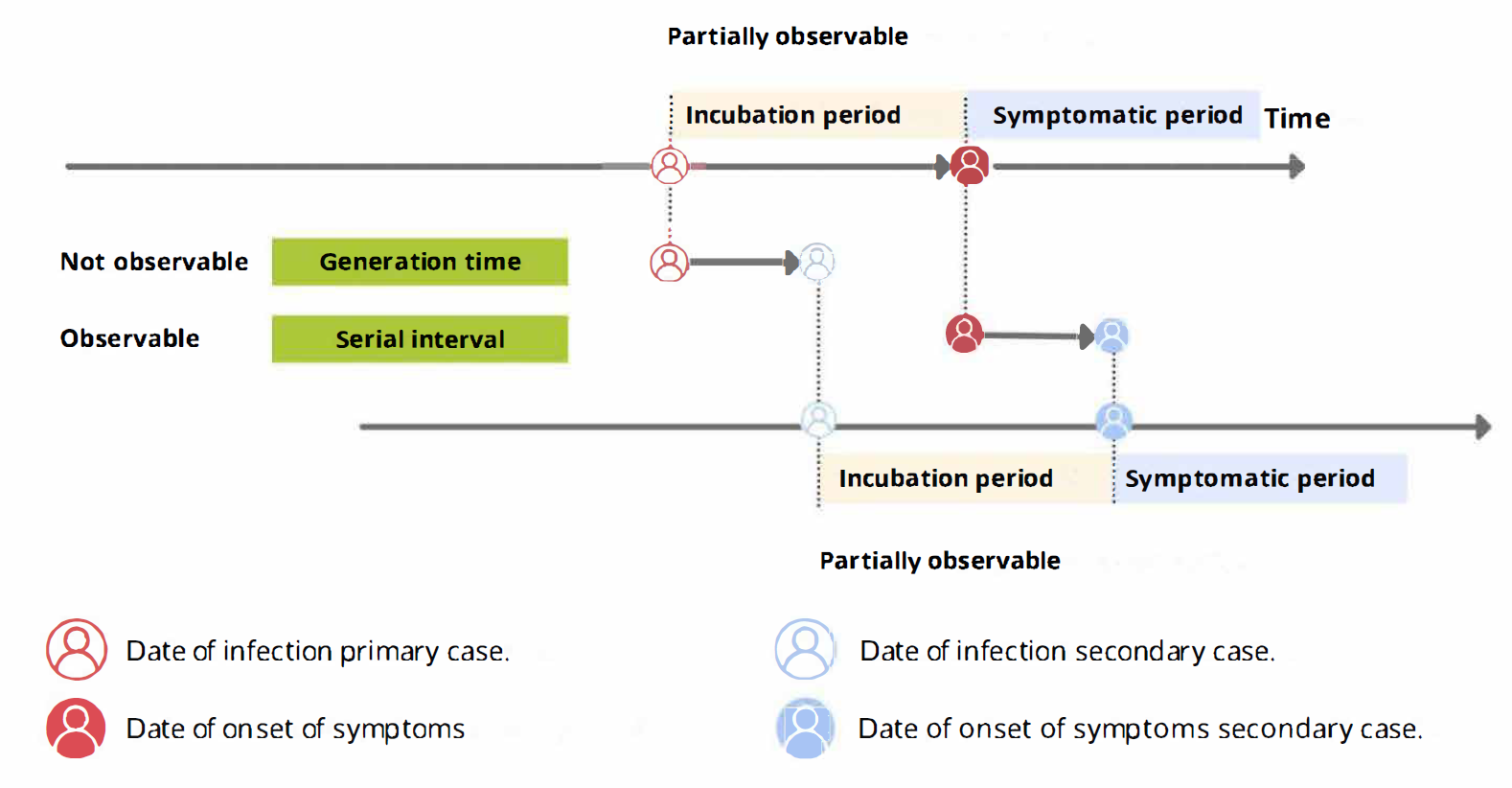

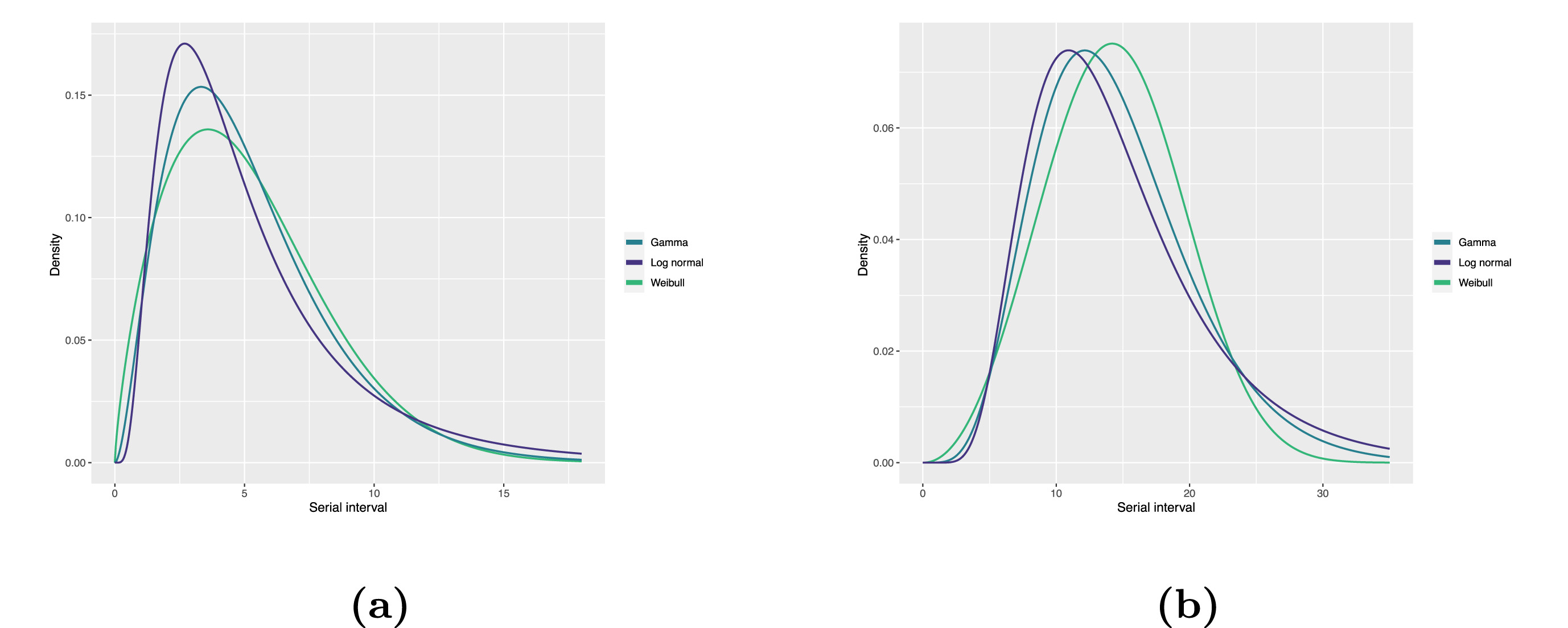

Callout

From time periods to probability distributions

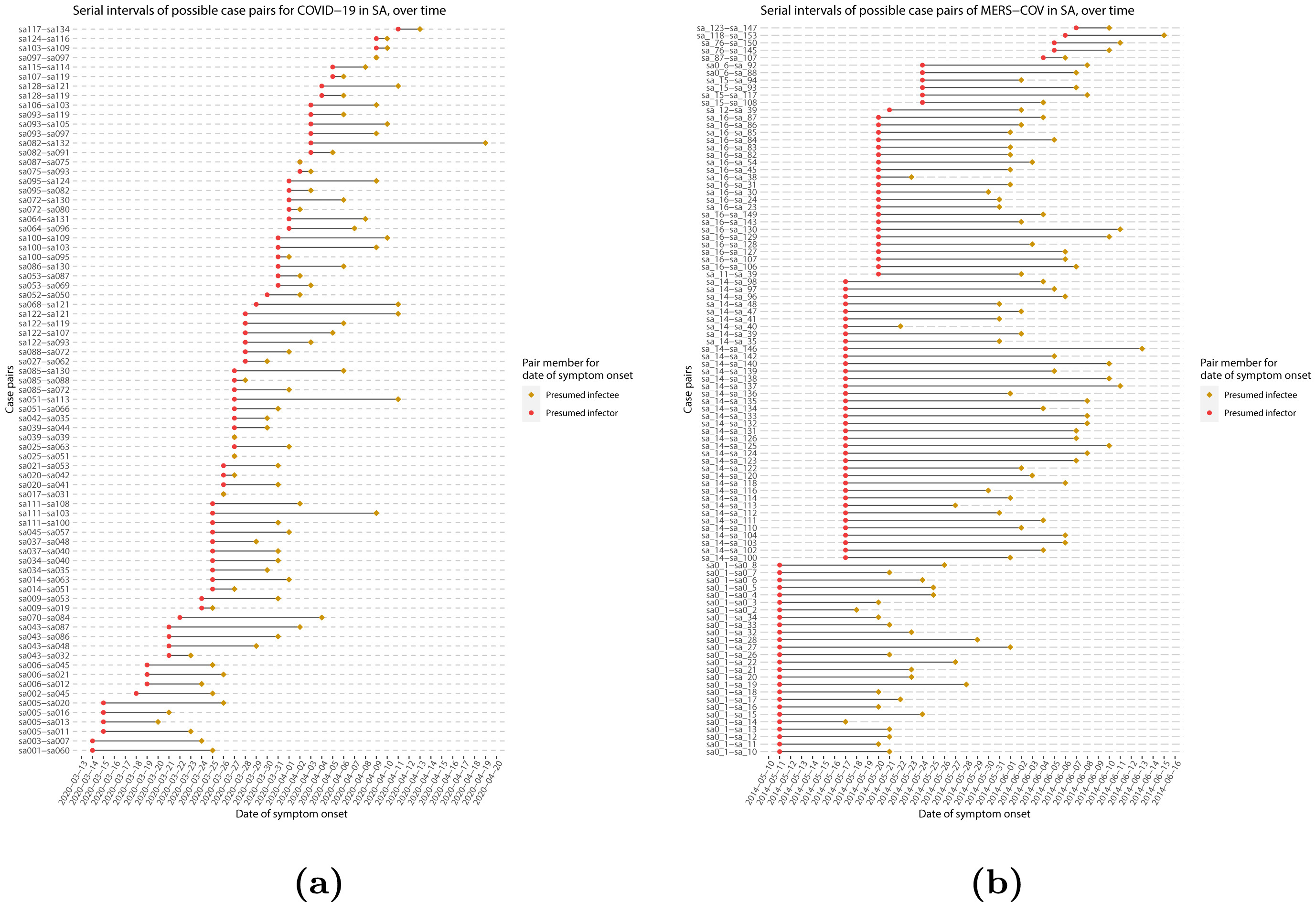

When we calculate the serial interval, we see that not all case pairs have the same time length. We will observe this variability for any case pair and individual time period.

To summarise these data from individual and pair time periods, we can find the statistical distributions that best fit the data (McFarland et al., 2023).

Statistical distributions are summarised in terms of their summary statistics like the location (mean and percentiles) and spread (variance or standard deviation) of the distribution, or with their distribution parameters that inform about the form (shape and rate/scale) of the distribution. These estimated values can be reported with their uncertainty (95% confidence intervals).

| Gamma | mean | shape | rate/scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| MERS-CoV | 14.13(13.9–14.7) | 6.31(4.88–8.52) | 0.43(0.33–0.60) |

| COVID-19 | 5.1(5.0–5.5) | 2.77(2.09–3.88) | 0.53(0.38–0.76) |

| Weibull | mean | shape | rate/scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| MERS-CoV | 14.2(13.3–15.2) | 3.07(2.64–3.63) | 16.1(15.0–17.1) |

| COVID-19 | 5.2(4.6–5.9) | 1.74(1.46–2.11) | 5.83(5.08–6.67) |

| Log normal | mean | mean-log | sd-log |

|---|---|---|---|

| MERS-CoV | 14.08(13.1–15.2) | 2.58(2.50–2.68) | 0.44(0.39–0.5) |

| COVID-19 | 5.2(4.2–6.5) | 1.45(1.31–1.61) | 0.63(0.54–0.74) |

From the cases object we can use:

-

dplyr::mutate()to transform thereporting_delayclass object from<time>to<numeric>, -

dplyr::filter()to keep the positive values, -

dplyr::pull()to extract a single column, -

fitdistrplus::fitdist()to fit a probability distribution using Maximum Likelihood. We can test distributions like the Log Normal ("lnorm"),"gamma", or"weibull".

R

cases %>%

dplyr::select(case_id, date_of_onset, date_of_hospitalisation) %>%

dplyr::mutate(reporting_delay = date_of_hospitalisation - date_of_onset) %>%

dplyr::mutate(reporting_delay_num = as.numeric(reporting_delay)) %>%

dplyr::filter(reporting_delay_num > 0) %>%

dplyr::pull(reporting_delay_num) %>%

fitdistrplus::fitdist(distr = "lnorm")

OUTPUT

Fitting of the distribution ' lnorm ' by maximum likelihood

Parameters:

estimate Std. Error

meanlog 1.0488098 0.06866105

sdlog 0.8465102 0.04855039Use summary() to find goodness-of-fit statistics from

the Maximum likelihood. Use plot() to visualize the fitted

density function and other quality control plots.

Now we can do inferences from the probability distribution fitted to the epidemiological delay! Want to learn how? Read the “Show details” :)

Making inferences from probability distributions

If you need it, read in detail about the R probability functions for the normal distribution, each of its definitions and identify in which part of a distribution they are located!

Each probability distribution has a unique set of

parameters and probability functions.

Read the Distributions

in the stats package or ?stats::Distributions to find

the ones available in R.

For example, assuming that the reporting delay follows a Log

Normal distribution, we can use plnorm() to

calculate the probability of observing a reporting delay of 14 days or

less:

R

plnorm(q = 14, meanlog = 1.0488098, sdlog = 0.8465102)

OUTPUT

[1] 0.9698499Or the amount of time by which 99% of symptomatic individuals are expected to be reported in the hospitalization record:

R

qlnorm(p = 0.99, meanlog = 1.0488098, sdlog = 0.8465102)

OUTPUT

[1] 20.45213To interactively explore probability distributions, their parameters and access to their distribution functions, we suggest to explore a shinyapp called The Distribution Zoo: https://ben18785.shinyapps.io/distribution-zoo/

Checklist

Let’s review some operators used until now:

- Assignment

<-assigns a value to a variable from right to left. - Double colon

::to call a function from a specific package. - Pipe

%>%to structure sequences of data operations left-to-right

We need to add two more to the list:

- Dollar sign

$ - Square brackets

[]

Last step is to access to this parameters. Most modeling outputs from

R functions will be stored as list class objects. In R, the

dollar sign operator $ is used to access elements (like

columns) within a data frame or list by name, allowing for easy

retrieval of specific components.

Testimonial

A code completion tip

If we write the square brackets [] next

to the object reporting_delay_fit$estimate[], within

[] we can use the Tab key ↹ for code

completion feature

This gives quick access to "meanlog" and

"sdlog". We invite you to try this out in code chunks and

the R console!

R

# 1. Place the cursor within the square brackets

# 2. Use the Tab key

# 3. Explore the completion list

# 4. Select for "meanlog" or "sdlog"

reporting_delay_fit$estimate[]

Callout

Estimating epidemiological delays is CHALLENGING!

Epidemiological delays need to account for biases like censoring, right truncation, or epidemic phase (Charniga et al., 2024).

Additionally, at the beginning of an outbreak, limited data or resources exist to perform this during a real-time analysis. Until we have more appropriate data for the specific disease and region of the ongoing outbreak, we can reuse delays from past outbreaks from the same pathogens or close in its phylogeny, independent of the area of origin.

In the following tutorial episodes, we will:

- Efficiently clean and produce epidemic curves to explore patterns of disease spread by difference group and time aggregates. Find more in Tutorials Early!

- Access to epidemiological delay distributions to estimate delay-adjusted transmission and severity metrics (e.g. reproduction number and case fatality risk). Find more in Tutorials Middle!

- Use parameter values like the basic reproduction number, and delays like the latent period and infectious period to simulate transmission trajectories and intervention scenarios. Find more in Tutorials Late!

Challenges

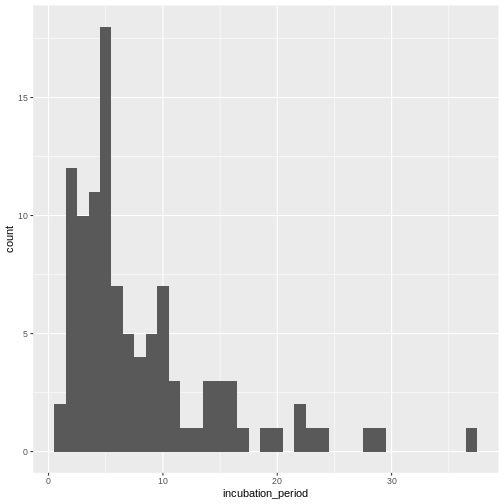

Challenge

Relevant delays when estimating transmission

Review the definition of the incubation period in our glossary page.

Calculate the summary statistics of the incubation period distribution observed in the line list.

Visualize the distribution of the incubation period from the line list.

Fit a log-normal distribution to get the probability distribution parameters of the the observed incubation period.

(Optional) Infer the time by which 99% of infected individuals are expected to show symptoms.

Calculate the summary statistics:

R

cases %>%

dplyr::select(case_id, date_of_infection, date_of_onset) %>%

dplyr::mutate(incubation_period = date_of_onset - date_of_infection) %>%

skimr::skim(incubation_period)

| Name | Piped data |

| Number of rows | 166 |

| Number of columns | 4 |

| _______________________ | |

| Column type frequency: | |

| difftime | 1 |

| ________________________ | |

| Group variables | None |

Variable type: difftime

| skim_variable | n_missing | complete_rate | min | max | median | n_unique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| incubation_period | 61 | 0.63 | 1 days | 37 days | 5 days | 25 |

Visualize the distribution:

R

cases %>%

dplyr::select(case_id, date_of_infection, date_of_onset) %>%

dplyr::mutate(incubation_period = date_of_onset - date_of_infection) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = incubation_period)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 1)

Fit a log-normal distribution:

R

incubation_period_dist <- cases %>%

dplyr::select(case_id, date_of_infection, date_of_onset) %>%

dplyr::mutate(incubation_period = date_of_onset - date_of_infection) %>%

mutate(incubation_period_num = as.numeric(incubation_period)) %>%

filter(!is.na(incubation_period_num)) %>%

pull(incubation_period_num) %>%

fitdistrplus::fitdist(distr = "lnorm")

incubation_period_dist

OUTPUT

Fitting of the distribution ' lnorm ' by maximum likelihood

Parameters:

estimate Std. Error

meanlog 1.8037993 0.07381350

sdlog 0.7563633 0.05219361(Optional) Infer the time by which 99% of infected individuals are expected to show symptoms:

R

qlnorm(

p = 0.99,

meanlog = incubation_period_dist$estimate["meanlog"],

sdlog = incubation_period_dist$estimate["sdlog"]

)

OUTPUT

[1] 35.28167With the distribution parameters of the incubation period we can infer the length of active monitoring or quarantine. Lauer et al., 2020 estimated the incubation period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases.

Challenge

Let’s create reproducible examples

(reprex). A reprex help us to communicate our

coding problems with software developers. Explore this Applied Epi

entry: https://community.appliedepi.org/t/how-to-make-a-reproducible-r-code-example/167

Create a reprex with your answer:

- What is the value of the CFR from the data set in the chuck below?

R

outbreaks::ebola_sim_clean %>%

pluck("linelist") %>%

as_tibble() %>%

...() # replace ... with downstream code

References

Cori, A. et al. (2019) Real-time outbreak analysis: Ebola as a case study - part 1 · Recon Learn, RECON learn. Available at: https://www.reconlearn.org/post/real-time-response-1 (Accessed: 06 November 2024).

Cori, A. et al. (2019) Real-time outbreak analysis: Ebola as a case study - part 2 · Recon Learn, RECON learn. Available at: https://www.reconlearn.org/post/real-time-response-2 (Accessed: 07 November 2024).