Modelling disease burden

Last updated on 2026-02-05 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can we model disease burden and healthcare demand?

Objectives

- Understand when mathematical models of transmission can be separated from models of burden

- Generate estimates of disease burden and healthcare demand using a burden model

Prerequisite

- Complete tutorial on Simulating transmission

Introduction

In previous tutorials we have used mathematical models to generate trajectories of infections, but we may also be interested in measures of disease burden. These measures could include:

- Health outcomes in the population (e.g., mild vs. severe infections)

- Healthcare system impacts (e.g., hospitalizations, ICU admissions)

- Economic impacts (e.g., productivity loss, healthcare costs)

In mathematical models, we can track disease burden in different ways:

- Integrated approach: Include burden compartments directly in the transmission model (e.g., hospital compartments in ODE models)

- Separated approach: First simulate transmission, then use the results to estimate burden

The choice between these approaches depends on whether burden affects transmission. For example:

- For Ebola, hospitalizations are important for transmission due to high-risk healthcare settings

- For many respiratory infections, severe illness typically occurs after the infectious period, so burden can be modeled separately

In this tutorial, we’ll focus on the separated approach, where we

first run an epidemic model to simulate infections, then use these

values to estimate disease burden as a follow-on analysis. We’ll use

{epidemics} to simulate disease trajectories,

socialmixr for social contact data, and

tidyverse for data manipulation and plotting.

R

library(epiparameter)

library(epidemics)

library(socialmixr)

library(tidyverse)

A burden model

We will extend the influenza example from the Simulating transmission tutorial

by using the output object to calculate hospitalizations

over time. Our approach has two main components:

- Transmission model: An SEIR model that generates new infections over time

- Burden model: Converts new infections to hospitalizations by accounting for delays between infection and hospitalization

To convert infections to hospitalizations, we need to consider:

- The probability that an infection leads to hospitalization (infection-hospitalization ratio, IHR)

- The time delay from infection to hospital admission

- The time spent in hospital before discharge

We’ll use epiparameter to define these delay distributions. The Gamma distribution is commonly used for these delays because:

- It’s flexible and can model various shapes

- It’s bounded at zero (negative delays don’t make sense)

- It’s supported by empirical data for many infectious diseases

R

new_cases <- new_infections(output, by_group = FALSE)

head(new_cases)

OUTPUT

Key: <time>

time new_infections

<num> <num>

1: 0 0.000000

2: 1 3.468452

3: 2 3.206039

4: 3 3.110541

5: 4 3.115967

6: 5 3.183338To convert the new infections to hospitalisations we need to parameter distributions to describe the following processes :

the time from infection to admission to hospital,

the time from admission to discharge from hospital.

We will use the function epiparameter() from

epiparameter package to define and store parameter

distributions for these processes.

R

# define delay parameters

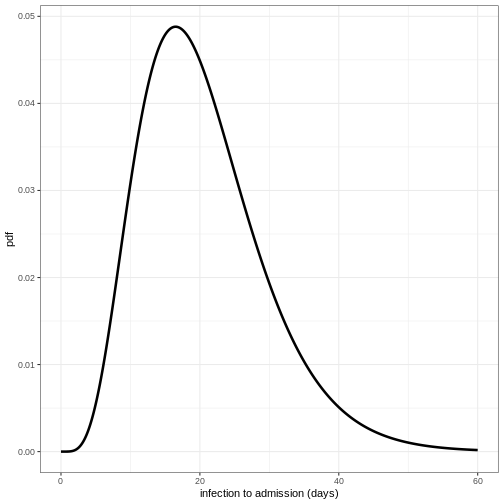

infection_to_admission <- epiparameter(

disease = "COVID-19",

epi_name = "infection to admission",

prob_distribution = create_prob_distribution(

prob_distribution = "gamma",

prob_distribution_params = c(shape = 5, scale = 4),

discretise = TRUE

)

)

# The shape and scale parameters were chosen based on data from COVID-19 studies

# showing a median time from infection to hospitalization of around 10 days

# with right-skewed distribution reflecting variability in disease progression

To visualise this distribution we can create a density plot :

R

x_range <- seq(0, 60, by = 0.1)

density_df <- data.frame(days = x_range,

density_admission = density(infection_to_admission,

x_range))

ggplot(data = density_df, aes(x = days, y = density_admission)) +

geom_line(linewidth = 1.2) +

theme_bw() +

labs(

x = "infection to admission (days)",

y = "pdf"

)

Define distribution for admission to discharge

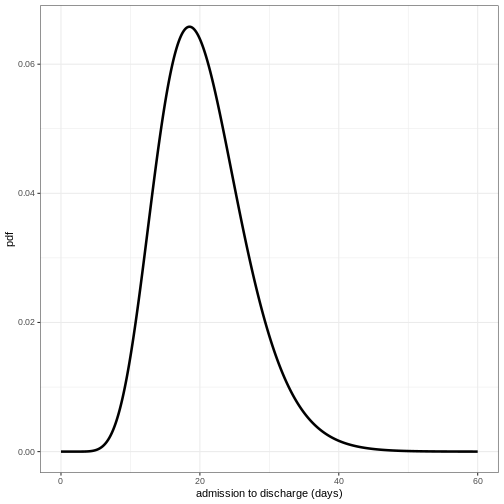

Using the function epiparameter() define the

distribution for admission to discharge as a Gamma distribution with

shape = 10 and scale = 2 and plot the density of this distribution.

R

admission_to_discharge <- epiparameter(

disease = "COVID-19",

epi_name = "admission to discharge",

prob_distribution = create_prob_distribution(

prob_distribution = "gamma",

prob_distribution_params = c(shape = 10, scale = 2),

discretise = TRUE

)

)

x_range <- seq(0, 60, by = 0.1)

density_df <- data.frame(days = x_range,

density_discharge = density(admission_to_discharge,

x_range))

ggplot(data = density_df, aes(x = days, y = density_discharge)) +

geom_line(linewidth = 1.2) +

theme_bw() +

labs(

x = "admission to discharge (days)",

y = "pdf"

)

To convert the new infections to number in hospital over time we will do the following:

- Calculate the expected numbers of new infections that will be hospitalised using the infection hospitalisation ratio (IHR)

- Calculate the estimated number of new hospitalisations at each point in time using the infection to admission distribution

- Calculate the estimated number of discharge at each point in time using the admission to discharge distribution

- Calculate the number in hospital at each point in time as the difference between the cumulative sum of hospital admissions and the cumulative sum of discharges so far.

1. Calculate the expected numbers of new hospitalisations using the infection hospitalisation ratio (IHR)

R

ihr <- 0.1 # infection-hospitalisation ratio

# This value is based on estimates from early COVID-19 data

# and represents the proportion of infections that require hospitalization

# calculate expected numbers with convolution:

hosp <- new_cases$new_infections * ihr

2. Calculate the estimated number of new hospitalisations using the infection to admission distribution

To estimate the number of new hospitalisations we use a method called convolution.

What is convolution?

If we want to know how people are admitted to hospital on day \(t\), then we need to add up the number of

people admitted on day \(t\) but

infected on day \(t-1\), day \(t-2\), day \(t-3\) etc. We therefore need to sum over

the distribution of delays from infection to admission. If \(f_j\) is the probability an infected

individual who will be hospitalised will be admitted to hospital \(j\) days later, and \(I_{t-j}\) is the number of individuals

infected on day \(t-j\), then the total

admissions on day \(t\) is equal to

\(\sum_j I_{t-j} f_j\). This type of

rolling calculation is known as a convolution (see this Wolfram

article for some mathematical detail). There are different methods

to calculate convolutions, but we will use the built in R function

convolve()to perform the summation efficiently from the

number of infections and the delay distribution.

The function convolve() requires inputs of two vectors

which will be convolved and type. Here we will specify

type = "open", this fills the vectors with 0s to ensure

they are the same length.

The inputs to be convolved are the expected number of infections that

will end up hospitalised (hosp) and the density values of

the distribution of infection to admission times. We will calculate the

density for the minimum possible value (0 days) up to the tail of the

distribution (here defined as the 99.9th quantile, i.e. it is very

unlikely any cases will be hospitalised after a delay this long).

Convolution requires one of the inputs to be reversed, in our case we will reverse the density distribution of infection to admission times. This is because if people infected earlier in time get admitted today, it means they’ve had a longer delay from infection to admission than someone infected more recently. In effect the infection to admission delay tells us how far we have to ‘rewind’ time to find previously new infections that are now showing up as hospital admissions.

R

# define tail of the delay distribution

tail_value_admission <- quantile(infection_to_admission, 0.999)

hospitalisations <- convolve(hosp,

rev(density(infection_to_admission,

0:tail_value_admission)),

type = "open")[seq_along(hosp)]

3. Calculate the estimated number of discharges

Using the same approach as above, we convolve the hospitalisations with the distribution of admission to discharge times to obtain the estimated number of new discharges.

R

tail_value_discharge <- quantile(admission_to_discharge, 0.999)

discharges <- convolve(hospitalisations, rev(density(admission_to_discharge,

0:tail_value_discharge)),

type = "open")[seq_along(hospitalisations)]

4. Calculate the number in hospital as the difference between the cumulative sum of hospitalisations and the cumulative sum of discharges

We can use the R function cumsum() to calculate the

cumulative number of hospitalisations and discharges. The difference

between these two quantities gives us the current number of people in

hospital at each time point.

R

# calculate the current number in hospital

in_hospital <- cumsum(hospitalisations) - cumsum(discharges)

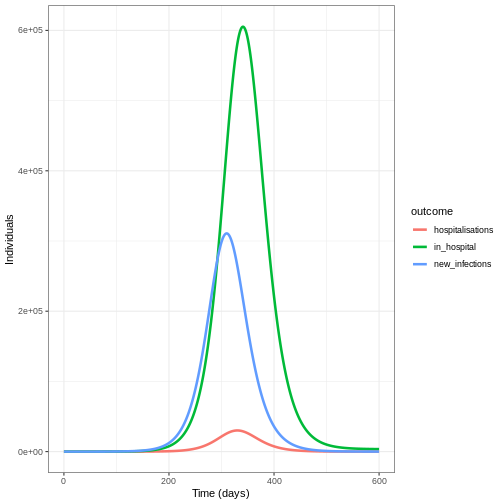

We create a data frame to plot our outcomes using

pivot_longer():

R

# create data frame

hosp_df <- cbind(new_cases, in_hospital = in_hospital,

hospitalisations = hospitalisations)

# pivot longer for plotting

hosp_df_long <- pivot_longer(hosp_df, cols = new_infections:hospitalisations,

names_to = "outcome", values_to = "value")

ggplot(data = hosp_df_long) +

geom_line(

aes(

x = time,

y = value,

colour = outcome

),

linewidth = 1.2

) +

theme_bw() +

labs(

x = "Time (days)",

y = "Individuals"

)

Summary

In this tutorial, we learned how to estimate hospitalizations based on daily new infections from a transmission model. This approach can be extended to other measures of disease burden, such as:

- ICU admissions

- Deaths

- Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs)

- Healthcare costs

These burden estimates are valuable for:

- Healthcare system planning

- Health economic analyses

- Policy decision-making

As a follow-up, you might be interested in this how-to guide, which shows how to estimate original infection events from reported hospitalizations or deaths over time.

Key Points

- Transmission models should include disease burden when it affects onward transmission

- Outputs of transmission models can be used as inputs to models of burden

- The Gamma distribution is commonly used to model delays in disease progression

- Convolution is a powerful tool for estimating disease burden from transmission model outputs