Estimation of outbreak severity

Last updated on 2026-02-09 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

Why do we estimate the clinical severity of an epidemic?

How can the Case Fatality Risk (CFR) be estimated early in an ongoing epidemic?

Objectives

Estimate the CFR from aggregated case data using cfr.

Estimate a delay-adjusted CFR using epiparameter and cfr.

Estimate a delay-adjusted severity for an expanding time series using cfr.

Prerequisites

This episode requires you to be familiar with:

Data science: Basic programming with R.

Epidemic theory: Delay distributions.

R packages installed: cfr, epiparameter, outbreaks, tidyverse.

Install packages if their are not already installed

R

# if {pak} is not installed, run: install.packages("pak")

pak::pak("cfr")

pak::pak("epiparameter")

pak::pak("tidyverse")

pak::pak("outbreaks")

If you have any error message, go to the main setup page.

Introduction

Common questions at the early stage of an epidemic include:

- What is the likely public health impact of the outbreak in terms of clinical severity?

- What are the most severely affected groups?

- Does the outbreak have the potential to cause a very severe pandemic?

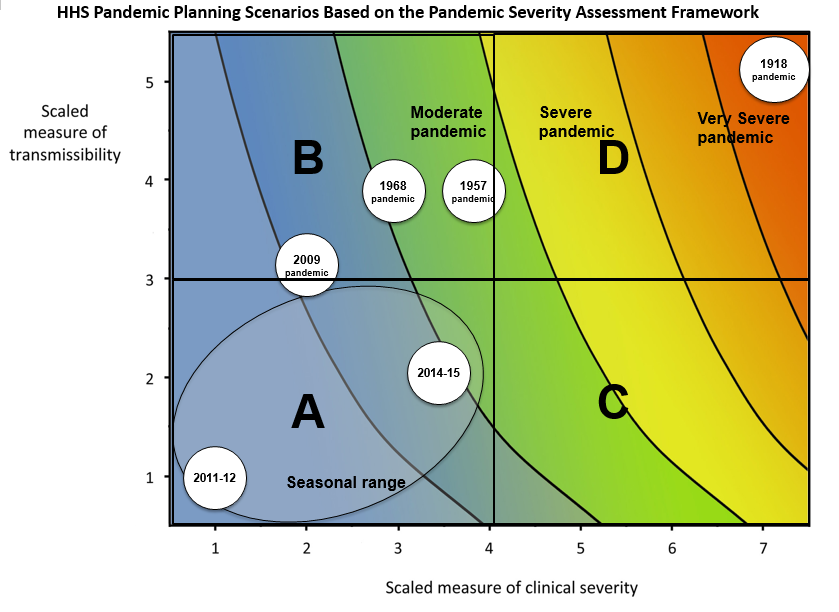

We can assess the pandemic potential of an epidemic with two critical measurements: the transmissibility and the clinical severity (Fraser et al., 2009, CDC, 2016).

One epidemiological approach to estimating the clinical severity is quantifying the Case Fatality Risk (CFR). CFR is the conditional probability of death given confirmed diagnosis, calculated as the ratio of the cumulative number of deaths from an infectious disease to the number of confirmed diagnosed cases. However, calculating this directly during the course of an epidemic tends to result in a naive or biased CFR given the time delay from onset to death, varying substantially as the epidemic progresses and stabilising at the later stages of the outbreak (Ghani et al., 2005).

More generally, estimating severity can be helpful even outside of a pandemic planning scenario and in the context of routine public health. Knowing whether an outbreak has or had a different severity from the historical record can motivate causal investigations, which could be intrinsic to the infectious agent (e.g., a new, more severe strain) or due to underlying factors in the population (e.g. reduced immunity or morbidity factors) (Lipsitch et al., 2015).

In this tutorial we are going to learn how to use the cfr package to calculate and adjust a CFR estimation using delay distributions from epiparameter or elsewhere, based on the methods developed by Nishiura et al., 2009, also, how we can reuse cfr functions for more severity measurements.

We’ll use the pipe %>% operator to connect functions,

so let’s also call to the tidyverse package:

R

library(cfr)

library(epiparameter)

library(tidyverse)

library(outbreaks)

The double-colon

The double-colon :: in R lets you call a specific

function from a package without loading the entire package into the

current environment.

For example, dplyr::filter(data, condition) uses

filter() from the dplyr package.

This helps us remember package functions and avoid namespace conflicts.

Discussion

Based on your experience:

- Share any previous outbreak in which you participated in its response.

Answer to these questions:

- How did you assess the clinical severity of the outbreak?

- What were the primary sources of bias?

- What did you do to take into account the identified bias?

- What complementary analysis would you do to solve the bias?

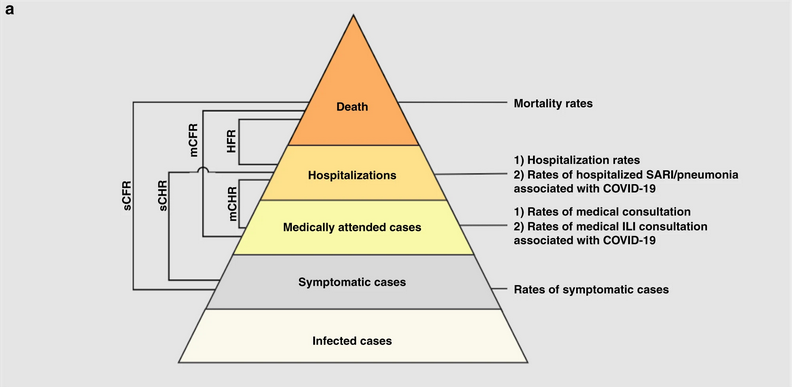

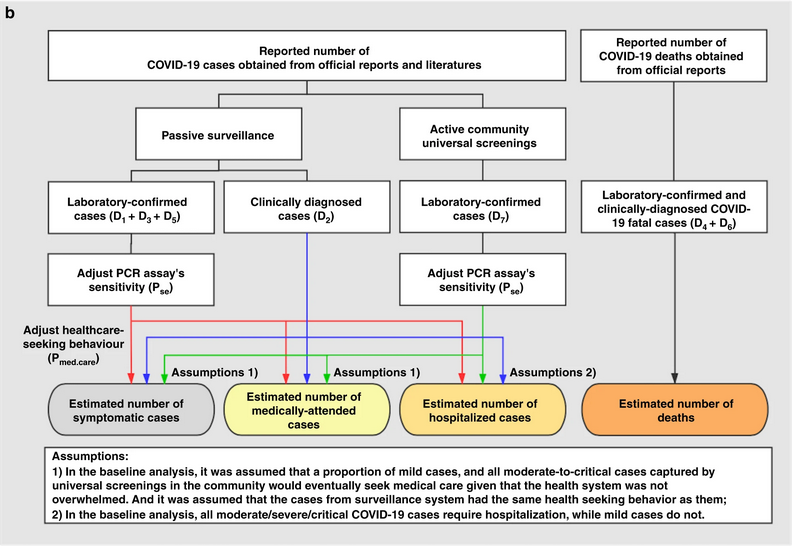

Data sources for clinical severity

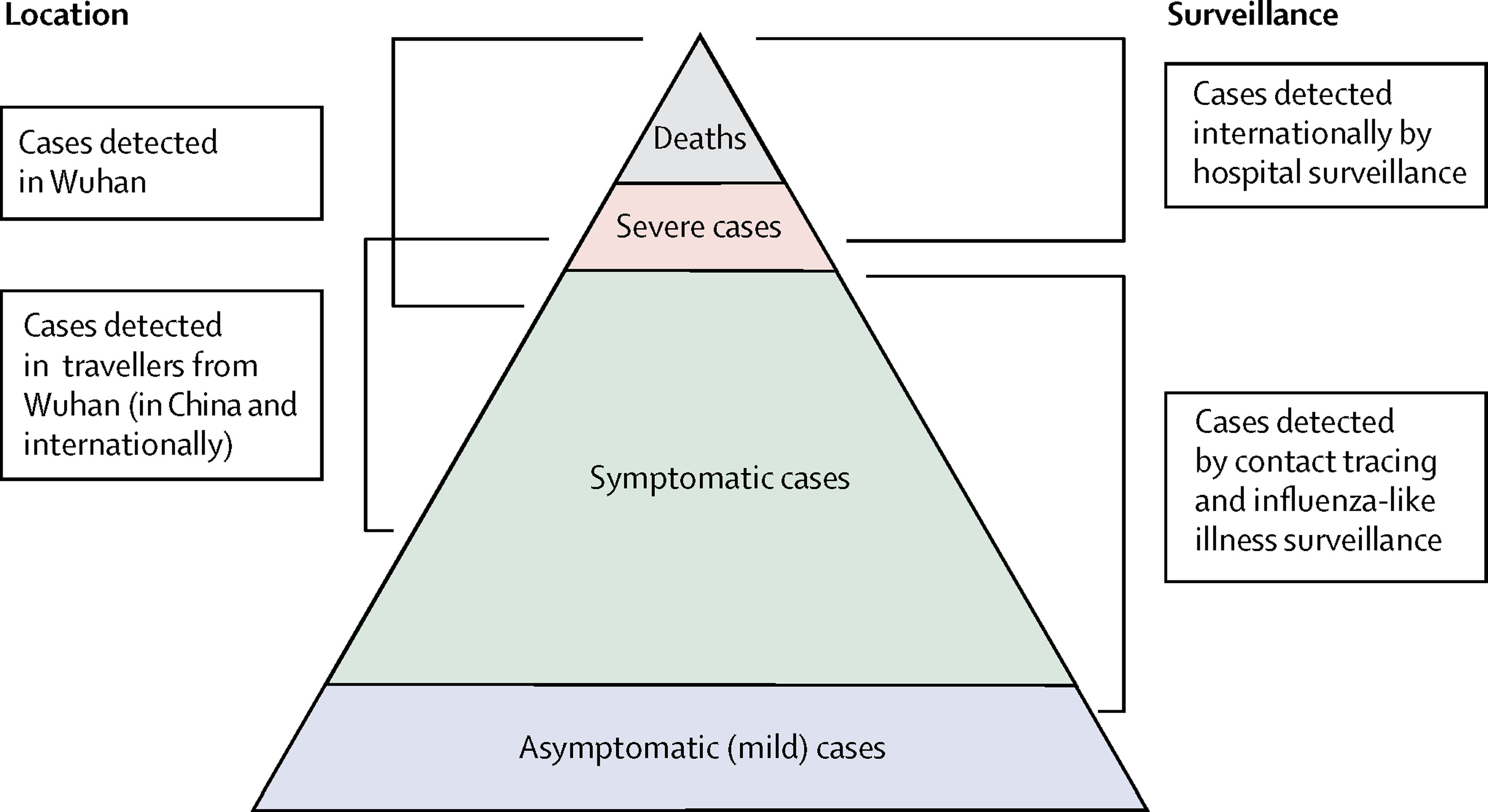

What data sources can we use to estimate the clinical severity of a disease outbreak? Verity et al., 2020 summarises the spectrum of COVID-19 cases:

- At the top of the pyramid, those who met the WHO case criteria for severe or critical cases would likely have been identified in the hospital setting, presenting with atypical viral pneumonia. These cases would have been identified in mainland China and among those categorised internationally as local transmission.

- Many more cases are likely to be symptomatic (i.e., with fever, cough, or myalgia) but might not require hospitalisation. These cases would have been identified through links to international travel to high-risk areas and through contact-tracing of contacts of confirmed cases. They might be identifiable through population surveillance of, for example, influenza-like illness.

- The bottom part of the pyramid represents mild (and possibly asymptomatic) cases. These cases might be identifiable through contact tracing and subsequently via serological testing.

Naive CFR

We measure disease severity in terms of case fatality risk (CFR). The CFR is interpreted as the conditional probability of death given confirmed diagnosis, calculated as the ratio of the cumulative number of deaths \(D_{t}\) to the cumulative number of confirmed cases \(C_{t}\) at a certain time \(t\). We can refer to the naive CFR (also crude or biased CFR, \(b_{t}\)):

\[ b_{t} = \frac{D_{t}}{C_{t}} \]

This calculation is naive because it tends to yield a biased and mostly underestimated CFR due to the time-delay from onset to death, only stabilising at the later stages of the outbreak.

To calculate the naive CFR, the cfr package requires an input data frame with three columns named:

datecasesdeaths

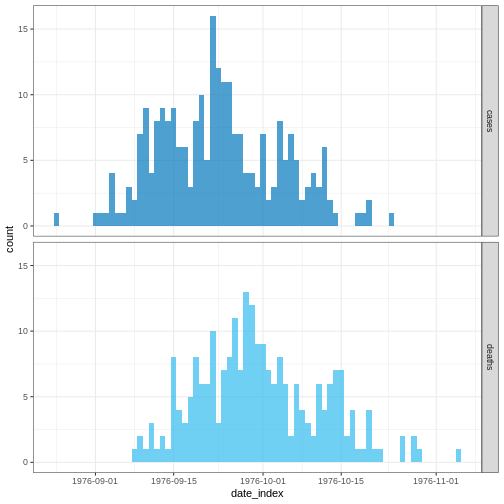

Let’s explore the ebola1976 dataset, included in {cfr},

which comes from the first Ebola outbreak in what was then called Zaire

(now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) in 1976, as analysed by

Camacho et al. (2014).

R

# Load the Ebola 1976 data provided with the {cfr} package

data("ebola1976")

# Plot the incidence of cases and death reports

ebola1976 %>%

incidence2::incidence(

date_index = "date",

counts = c("cases", "deaths")

) %>%

plot()

We’ll frame this episode under the context of an ongoing outbreak with only the first 30 days of data observed.

R

# Assume we only have the first 30 days of this data

ebola_30days <- ebola1976 %>%

dplyr::slice_head(n = 30) %>%

dplyr::as_tibble()

ebola_30days

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 30 × 3

date cases deaths

<date> <int> <int>

1 1976-08-25 1 0

2 1976-08-26 0 0

3 1976-08-27 0 0

4 1976-08-28 0 0

5 1976-08-29 0 0

6 1976-08-30 0 0

7 1976-08-31 0 0

8 1976-09-01 1 0

9 1976-09-02 1 0

10 1976-09-03 1 0

# ℹ 20 more rowsWe need aggregated incidence data

cfr reads aggregated incidence data.

This data input should be aggregated by day, which means one observation per day, containing the daily number of reported cases and deaths. Observations with zero or missing values should also be included, similar to time-series data.

Also, cfr currently works for daily data only, but not for other temporal units of data aggregation, e.g., weeks.

Checklist

When aggregating cases by day with incidence2, you can

adapt the data for cfr using

cfr::prepare_data() on <incidence2>

objects. For details and an example, consult the cfr

reference manual on preparing

common epidemiological data formats for CFR estimation.

When we apply cfr_static() to data

directly, we are calculating the naive CFR:

R

# Calculate the naive CFR for the first 30 days

cfr::cfr_static(data = ebola_30days)

OUTPUT

severity_estimate severity_low severity_high

1 0.4740741 0.3875497 0.5617606Challenge

Download the file sarscov2_cases_deaths.csv and read it into R.

Estimate the naive CFR.

Inspect the format of the data input.

- Does it contain daily data?

- Does the column names are as required by

cfr_static()? - How would you rename column names from a data frame?

We read the data input using readr::read_csv(). This

function recognize that the column date is a

<date> class vector.

R

# read data

# e.g.: if path to file is data/raw-data/ebola_cases.csv then:

sarscov2_input <-

readr::read_csv(here::here("data", "raw-data", "sarscov2_cases_deaths.csv"))

R

# Inspect data

sarscov2_input

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 93 × 3

date cases_jpn deaths_jpn

<date> <dbl> <dbl>

1 2020-01-20 1 0

2 2020-01-21 1 0

3 2020-01-22 0 0

4 2020-01-23 1 0

5 2020-01-24 1 0

6 2020-01-25 3 0

7 2020-01-26 3 0

8 2020-01-27 4 0

9 2020-01-28 6 0

10 2020-01-29 7 0

# ℹ 83 more rowsWe can use dplyr::rename() to adapt the external data to

fit the data input for cfr_static().

R

# Rename before Estimate naive CFR

sarscov2_input %>%

dplyr::rename(

cases = cases_jpn,

deaths = deaths_jpn

) %>%

cfr::cfr_static()

OUTPUT

severity_estimate severity_low severity_high

1 0.01895208 0.01828832 0.01963342Biases that affect CFR estimation

Two biases that affect CFR estimation

Lipsitch et al., 2015 describe two potential biases that can affect the estimation of CFR (and their potential solutions):

For diseases with a spectrum of clinical presentations, those cases that come to the attention of public health authorities and are registered into surveillance databases will typically be people with the most severe symptoms who seek medical care, are admitted to a hospital, or die.

Therefore, the CFR will typically be higher among detected cases than among the entire population of cases, given that the latter may include individuals with mild, subclinical, and (under some definitions of “case”) asymptomatic presentations.

During an ongoing epidemic, there is a delay between the time someone dies and the time their death is reported. Therefore, at any given moment in time, the list of cases includes people who will die and whose death has not yet occurred or has occurred but not yet been reported. Thus, dividing the cumulative number of reported deaths by the cumulative number of reported cases at a specific time point during an outbreak will underestimate the true CFR.

The key determinants of the magnitude of the bias are the epidemic growth rate and the distribution of delays from case-reporting to death-reporting; the longer the delays and the faster the growth rate, the greater the bias.

In this tutorial episode, we are going to focus on solutions to deal with this specific bias using cfr!

Improving an early epidemiological assessment of a delay-adjusted CFR is crucial for determining virulence, shaping the level and choices of public health intervention, and providing advice to the general public.

In 2009, during the swine-flu virus, Influenza A (H1N1), Mexico had an early biased estimation of the CFR. Initial reports from the government of Mexico suggested a virulent infection, whereas, in other countries, the same virus was perceived as mild (TIME, 2009).

In the USA and Canada, no deaths were attributed to the virus in the first ten days following the World Health Organization’s declaration of a public health emergency. Even under similar circumstances at the early stage of the global pandemic, public health officials, policymakers and the general public want to know the virulence of an emerging infectious agent.

Garske et al., 2009 assess the challenges to estimate the severity of this pandemic, emphasising that accurately capturing the cases for the denominator can improve the capacity to obtain informative CFR estimates.

Delay-adjusted CFR

Nishiura et al., 2009 developed a method that considers the time delay from the onset of symptoms to death.

Real-time outbreaks may have a number of deaths that are insufficient

to determine the time distribution between onset and death. Therefore,

we can estimate the distribution delay from historical

outbreaks or reuse the ones accessible via R packages like

epiparameter or {epireview}, which collect

them from published scientific literature. For a step-by-step guide,

read the tutorial episode on how to access

epidemiological delays.

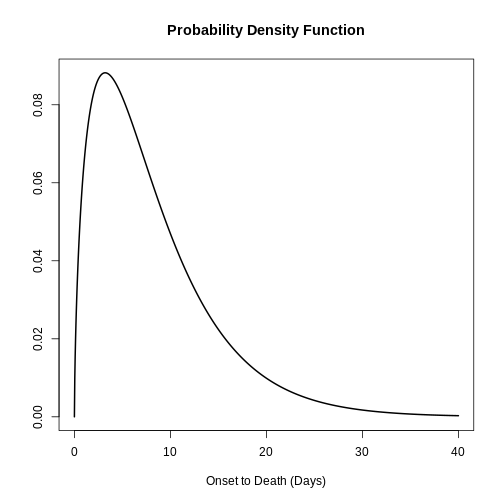

Let’s use epiparameter:

R

# Get delay distribution

onset_to_death_ebola <-

epiparameter::epiparameter_db(

disease = "Ebola",

epi_name = "onset_to_death",

single_epiparameter = TRUE

)

# Plot <epiparameter> object

plot(onset_to_death_ebola, xlim = c(0, 40))

To calculate the delay-adjusted CFR, we can use the

cfr_static() function with the data and

delay_density arguments.

R

# Calculate the delay-adjusted CFR

# for the first 30 days

cfr::cfr_static(

data = ebola_30days,

delay_density = function(x) density(onset_to_death_ebola, x)

)

OUTPUT

severity_estimate severity_low severity_high

1 0.9502 0.881 0.9861The delay-adjusted CFR indicated that the overall disease severity at the end of the outbreak or with the latest data available at the moment is 0.9502 with a 95% confidence interval between 0.881 and 0.9861, slightly higher than the naive one.

How does {cfr} work?

If you want to gain familiarity and learn how delays are accounted for when estimating CFR, you can read the episode on How to adjust the CFR for delays in the “More Resources” section of this tutorial’s website.

To correct the bias arising from cases whose outcomes are not yet known at the time of estimation, cfr accounts for the probability that a case’s outcome becomes known after a certain delay.

It does so by relating \(D_t\) to the incidence function \(c_t\) (i.e., the number of new confirmed cases on day t) and the conditional probability density function \(f_s\) of the time from onset to death, given death.

\[ D_t = p_t \times \sum_{i = 0}^t\sum_{j = 0}^\infty c_i f_{j - i} \]

Here, \(D_t\) is the cumulative number of deaths up to time t, and \(p_t\) is the realized proportion of confirmed cases that die from the infection (i.e., the unbiased case fatality risk, or CFR).

The term \(\sum_{i = 0}^t\sum_{j =

0}^\infty c_i f_{j - i}\) represents the total expected

number of cases with known outcomes by time t. It

sums all incident cases \(c_i\), each

weighted by the probability density function \(f_{j−i}\) that their outcomes become known

after a delay of \(j−i\) days.

On each analysis day, cfr computes, for each case, the

expected number of outcomes by time t.

When using <epiparameter> class objects, the function

density() can be applied to obtain the corresponding

probability density function for each case on each day.

For example, by day 1, the expected outcomes are equal to:

- the number of observed cases on day 1 times the density at day 0.

R

# By Day 1, the expected outcomes are:

ebola_30days$cases[1] *

density(onset_to_death_ebola, at = 0)

OUTPUT

[1] 0By day 2, the expected outcomes are equal to:

- the number of observed cases on day 1 times the density at day 1, plus

- the number of observed cases on day 2 times the density at day 0

R

# By Day 2, the expected outcomes are:

ebola_30days$cases[1] *

density(onset_to_death_ebola, at = 1) +

ebola_30days$cases[2] *

density(onset_to_death_ebola, at = 0)

OUTPUT

[1] 0.06495664By day 3, the expected outcomes are equal to:

- the number of observed cases on day 1 times the density at day 2, plus

- the number of observed cases on day 2 times the density at day 1, plus

- the number of observed cases on day 3 times the density at day 0.

R

# By Day 3, the expected outcomes are:

ebola_30days$cases[1] *

density(onset_to_death_ebola, at = 2) +

ebola_30days$cases[2] *

density(onset_to_death_ebola, at = 1) +

ebola_30days$cases[3] *

density(onset_to_death_ebola, at = 0)

OUTPUT

[1] 0.08295091Notice that the most recently observe cases start the delay

distribution from 0 the others continue with the following

day.

Since the input value in at varies by day for each case

(at = 0, at = 1, at = 2, …), the

density() needs to be expressed as a function of x.

cfr will then draw values accordingly, as shown

below:

R

# {cfr} uses the density of the distribution at different values of x

function(x) density(onset_to_death_ebola, at = x)

Internally, the function cfr::estimate_outcomes()

performs this calculation:

R

cfr::estimate_outcomes(

data = ebola_30days,

delay_density = function(x) density(onset_to_death_ebola, at = x)

) %>%

slice_head(n = 3) %>%

pull(estimated_outcomes)

OUTPUT

[1] 0.00000000 0.06495664 0.08295091Use the epiparameter class

When using an <epiparameter> class object we can

use this expression as a template:

function(x) density(<EPIPARAMETER_OBJECT>, x)

For distribution functions with parameters not available in epiparameter, we suggest you two alternatives:

Create an

<epiparameter>class object, to plug into other R packages of the outbreak analytics pipeline. Read the reference documentation ofepiparameter::epiparameter(), orRead cfr vignette for a primer on working with delay distributions.

For cfr_static() and all functions in the

cfr_*() family, the most appropriate choice to use are

discrete distributions. This is because

cfr operates on count data in discrete time: daily case

and death counts.

We can assume that evaluating the Probability Distribution Function (PDF) of a continuous distribution is equivalent to the Probability Mass Function (PMF) of the equivalent discrete distribution.

However, this assumption may not be appropriate for distributions

with larger peaks. For instance, diseases with an onset-to-death

distribution that is strongly peaked with a low variance. In such cases,

the average disparity between the PDF and PMF is expected to be more

pronounced compared to distributions with broader spreads. One way to

deal with this is to discretise the continuous distribution using

epiparameter::discretise() to an

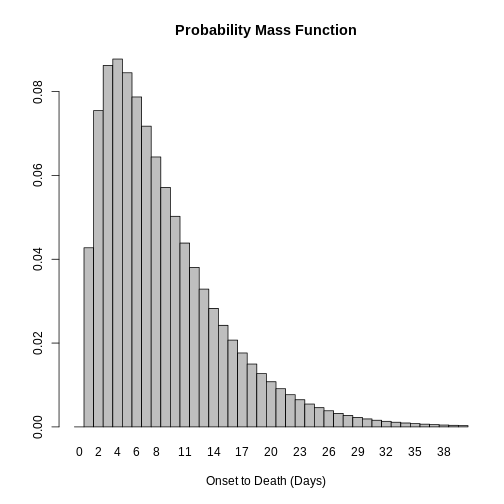

<epiparameter> object.

R

onset_to_death_ebola %>%

epiparameter::discretise() %>%

plot(xlim = c(0, 40))

Challenge

Use the same file from the previous challenge (sarscov2_cases_deaths.csv).

Estimate the delay-adjusted CFR using the appropriate distribution delay. Then:

- Compare the naive and the delay-adjusted CFR solutions!

- Find the appropriate

<epiparameter>object!

We use epiparameter to access a delay distribution for the SARS-CoV-2 aggregated incidence data:

R

library(epiparameter)

sarscov2_delay <-

epiparameter::epiparameter_db(

disease = "covid",

epi_name = "onset to death",

single_epiparameter = TRUE

)

We read the data input using readr::read_csv(). This

function recognize that the column date is a

<date> class vector.

R

# read data

# e.g.: if path to file is data/raw-data/ebola_cases.csv then:

sarscov2_input <-

readr::read_csv(here::here("data", "raw-data", "sarscov2_cases_deaths.csv"))

R

# Inspect data

sarscov2_input

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 93 × 3

date cases_jpn deaths_jpn

<date> <dbl> <dbl>

1 2020-01-20 1 0

2 2020-01-21 1 0

3 2020-01-22 0 0

4 2020-01-23 1 0

5 2020-01-24 1 0

6 2020-01-25 3 0

7 2020-01-26 3 0

8 2020-01-27 4 0

9 2020-01-28 6 0

10 2020-01-29 7 0

# ℹ 83 more rowsWe can use dplyr::rename() to adapt the external data to

fit the data input for cfr_static().

R

# Rename before Estimate naive CFR

sarscov2_input %>%

dplyr::rename(

cases = cases_jpn,

deaths = deaths_jpn

) %>%

cfr::cfr_static(

delay_density = function(x) density(sarscov2_delay, x)

)

OUTPUT

severity_estimate severity_low severity_high

1 0.0734 0.071 0.0759Interpret the comparison between the naive and delay-adjusted CFR estimates.

An early-stage CFR estimate

The naive estimate is useful to get an overall severity estimate of the outbreak (so far). Once the outbreak has ended or has progressed such that more deaths are reported, the estimated CFR is then closest to the ‘true’ unbiased CFR.

On the other hand, the delay-adjusted estimate can assess the severity of an emerging infectious disease earlier than the biased or naive CFR, during an epidemic.

We can explore the early determination of the

delay-adjusted CFR using the cfr_rolling()

function.

Callout

cfr_rolling() is a utility function that automatically

calculates CFR for each day of the outbreak with the data available up

to that day, saving the user time.

cfr_rolling() shows the estimated CFR on each outbreak

day, given that future data on cases and deaths is unavailable at the

time. The final value of cfr_rolling() estimates is

identical to cfr_static() on the same data.

R

# for all the 73 days in the Ebola dataset

# Calculate the rolling daily naive CFR

rolling_cfr_naive <- cfr::cfr_rolling(data = ebola1976)

OUTPUT

`cfr_rolling()` is a convenience function to help understand how additional data influences the overall (static) severity. Use `cfr_time_varying()` instead to estimate severity changes over the course of the outbreak.R

# for all the 73 days in the Ebola dataset

# Calculate the rolling daily delay-adjusted CFR

rolling_cfr_adjusted <- cfr::cfr_rolling(

data = ebola1976,

delay_density = function(x) density(onset_to_death_ebola, x)

)

OUTPUT

`cfr_rolling()` is a convenience function to help understand how additional data influences the overall (static) severity. Use `cfr_time_varying()` instead to estimate severity changes over the course of the outbreak.OUTPUT

Some daily ratios of total deaths to total cases with known outcome are below 0.01%: some CFR estimates may be unreliable.FALSEWith utils::tail(), we show that the latest CFR

estimates. The naive and delay-adjusted estimates have overlapping

ranges of 95% confidence intervals.

R

# Print the tail of the data frame

utils::tail(rolling_cfr_naive)

utils::tail(rolling_cfr_adjusted)

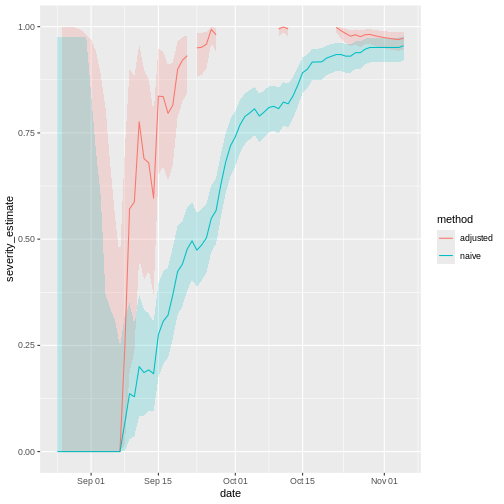

Now, let’s visualise both results in a time series. How would the naive and delay-adjusted CFR estimates perform in real time?

R

# bind by rows both output data frames

dplyr::bind_rows(

list(

naive = rolling_cfr_naive,

adjusted = rolling_cfr_adjusted

),

.id = "method"

) %>%

# visualise both adjusted and unadjusted rolling estimates

ggplot() +

geom_ribbon(

aes(

date,

ymin = severity_low,

ymax = severity_high,

fill = method

),

alpha = 0.2, show.legend = FALSE

) +

geom_line(

aes(date, severity_estimate, colour = method)

)

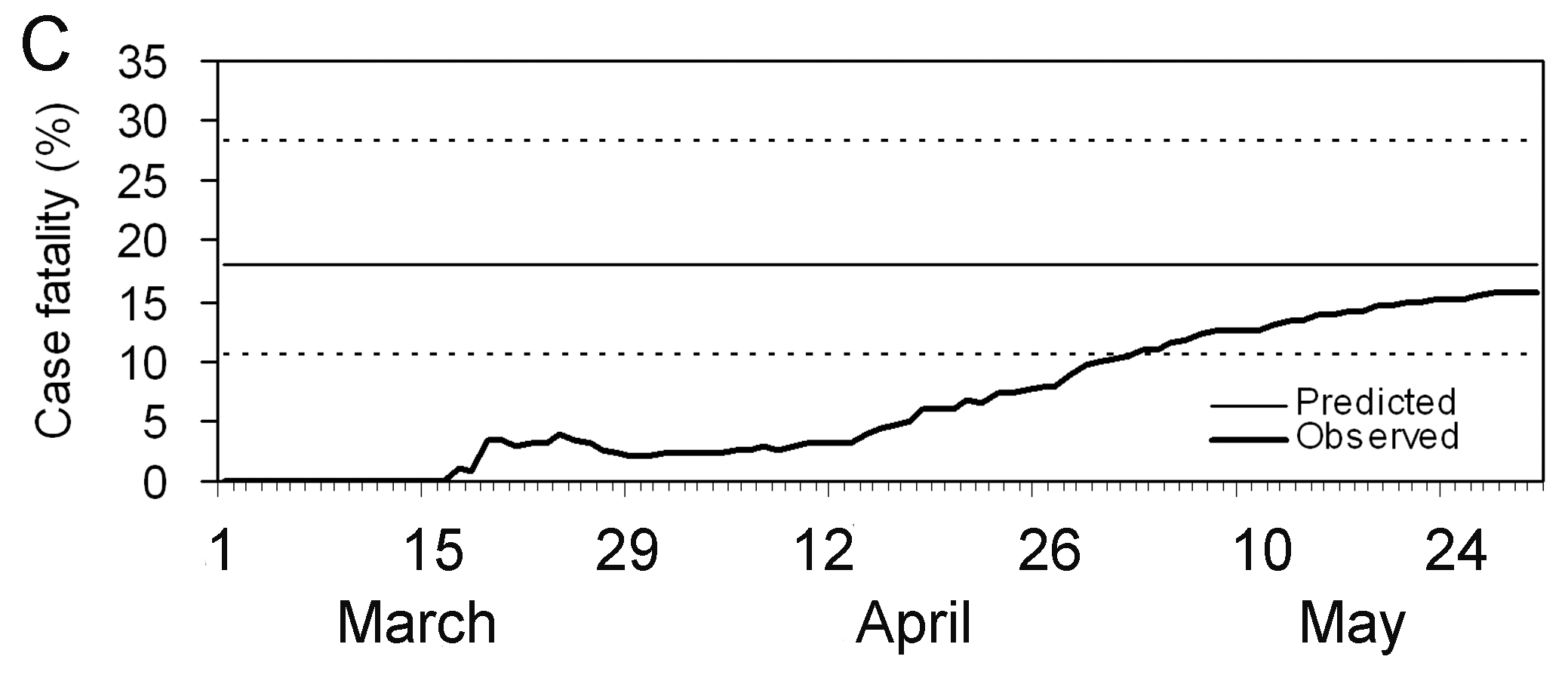

The horizontal line represents the delay-adjusted CFR estimated at the outbreak’s end. The dotted line means the estimate has a 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

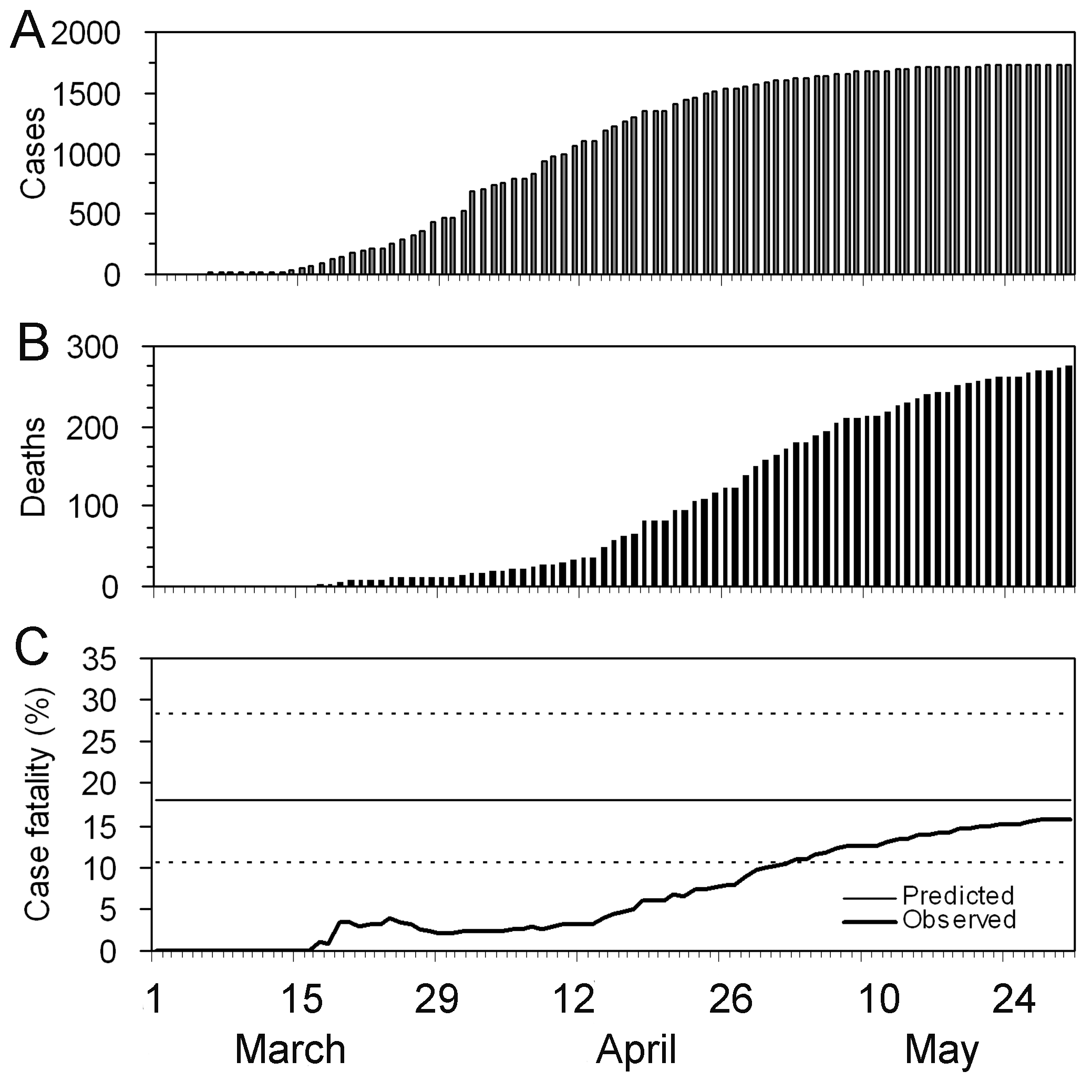

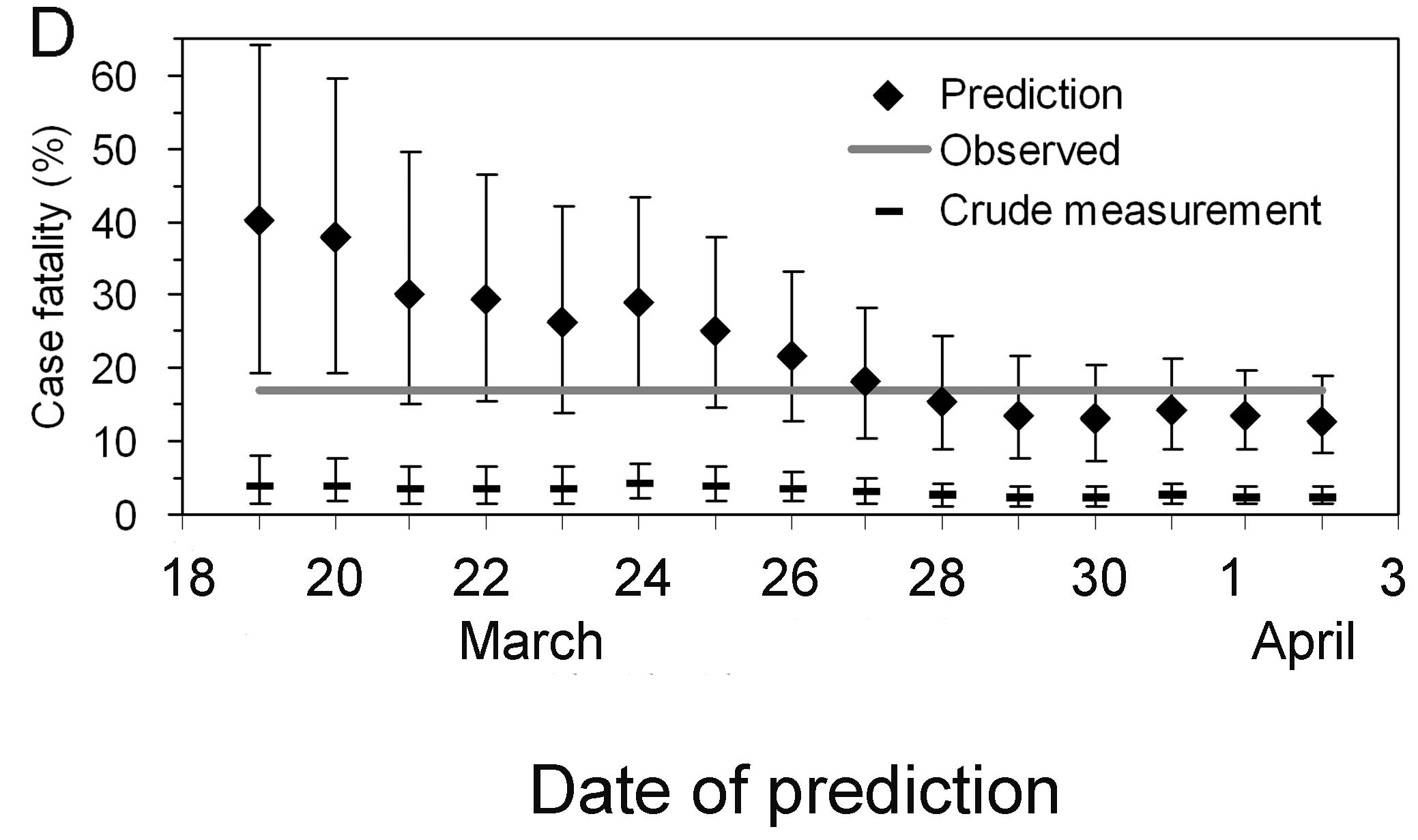

Notice that this delay-adjusted calculation is particularly useful when an epidemic curve of confirmed cases is the only data available (i.e. when individual data from onset to death are unavailable, especially during the early stage of the epidemic). When there are few deaths or none at all, an assumption has to be made for the delay distribution from onset to death, e.g. from literature based on previous outbreaks. Nishiura et al., 2009 depict this in the figures with data from the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong, 2003.

Figures A and B show the cumulative numbers of cases and deaths of SARS, and Figure C shows the observed (biased) CFR estimates as a function of time, i.e. the cumulative number of deaths over cases at time \(t\). Due to the delay from the onset of symptoms to death, the biased estimate of CFR at time \(t\) underestimates the realised CFR at the end of an outbreak (i.e. 302/1755 = 17.2 %).

Nevertheless, even by only using the observed data for the period

March 19 to April 2, cfr_static() can yield an appropriate

prediction (Figure D), e.g. the delay-adjusted CFR at March 27 is 18.1 %

(95% CI: 10.5, 28.1). An overestimation is seen in the very early stages

of the epidemic, but the 95% confidence limits in the later stages

include the realised CFR (i.e. 17.2 %).

Interpret the early-stage CFR estimate

Based on the figure above:

- How much difference in days is between the date in which the 95% CI of the estimated delay-adjusted CFR vs naive CFR cross with the CFR estimated at the end of the outbreak?

Discuss:

- What are the Public health policy implications of having a delay-adjusted CFR estimate?

We can use either visual inspection or analysis of the output data frames.

Checklist

With cfr, we estimate the CFR as the proportion of deaths among confirmed cases.

By only using confirmed cases, it is clear that all cases that do not seek medical treatment or are not notified will be missed, as well as all asymptomatic cases. This means that the CFR estimate is higher than the proportion of deaths among the infected.

cfr method aims to obtain an unbiased estimator “well before” observing the entire course of the outbreak. For this, cfr uses the underestimation factor \(u_{t}\) to estimate the unbiased CFR \(p_{t}\) using maximum-likelihood methods, given the sampling process defined by Nishiura et al., 2009.

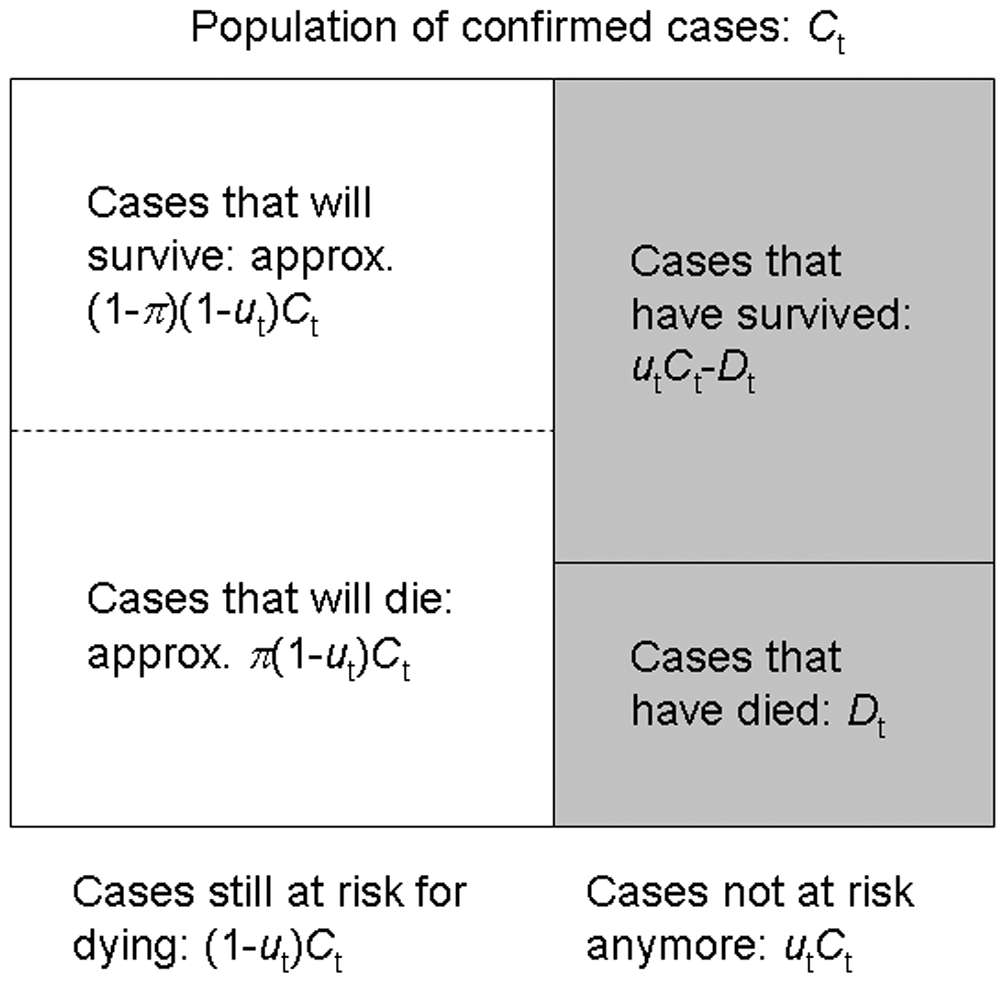

From aggregated incidence data, at time \(t\) we know the cumulative number of confirmed cases and deaths, \(C_{t}\) and \(D_{t}\), and wish to estimate the unbiased CFR \(\pi\), by way of the factor of underestimation \(u_{t}\).

If we knew the factor of underestimation \(u_{t}\) we could specify the size of the population of confirmed cases no longer at risk (\(u_{t}C_{t}\), shaded), although we do not know which surviving individuals belong to this group. A proportion \(\pi\) of those in the group of cases still at risk (size \((1- u_{t})C_{t}\), unshaded) is expected to die.

Because each case no longer at risk had an independent probability of dying, \(\pi\), the number of deaths, \(D_{t}\), is a sample from a binomial distribution with sample size \(u_{t}C_{t}\), and probability of dying \(p_{t}\) = \(\pi\).

This is represented by the following likelihood function to obtain the maximum likelihood estimate of the unbiased CFR \(p_{t}\) = \(\pi\):

\[ {\sf L}(\pi | C_{t},D_{t},u_{t}) = \log{\dbinom{u_{t}C_{t}}{D_{t}}} + D_{t} \log{\pi} + (u_{t}C_{t} - D_{t})\log{(1 - \pi)}, \]

This estimation is performed by the internal function

?cfr:::estimate_severity().

- The delay-adjusted CFR does not address all sources of error in data like the underdiagnosis of infected individuals.

Challenges

More severity measures

Suppose we need to assess the clinical severity of the epidemic in a context different from surveillance data, like the severity among cases that arrive at hospitals or cases you collected from a representative serological survey.

Using cfr, we can change the inputs for the numerator

(cases) and denominator (deaths) to estimate

more severity measures like the Infection fatality risk (IFR) or the

Hospitalisation Fatality Risk (HFR). We can follow this analogy:

If for a Case fatality risk (CFR), we require:

- case and death incidence data, with a

- case-to-death delay distribution (or close approximation, such as symptom onset-to-death).

Then, the Infection fatality risk (IFR) requires:

- infection and death incidence data, with an

- exposure-to-death delay distribution (or close approximation).

Similarly, the Hospitalisation Fatality Risk (HFR) requires:

- hospitalisation and death incidence data, and a

- hospitalisation-to-death delay distribution.

Yang et al., 2020 summarises different definitions and data sources:

- sCFR symptomatic case-fatality risk,

- sCHR symptomatic case-hospitalisation risk,

- mCFR medically attended case-fatality risk,

- mCHR medically attended case-hospitalisation risk,

- HFR hospitalisation-fatality risk.

Aggregated data differ from linelists

Aggregated incidence data differs from linelist data, where each observation contains individual-level data.

R

outbreaks::ebola_sierraleone_2014 %>% as_tibble()

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 11,903 × 8

id age sex status date_of_onset date_of_sample district chiefdom

<int> <dbl> <fct> <fct> <date> <date> <fct> <fct>

1 1 20 F confirmed 2014-05-18 2014-05-23 Kailahun Kissi Teng

2 2 42 F confirmed 2014-05-20 2014-05-25 Kailahun Kissi Teng

3 3 45 F confirmed 2014-05-20 2014-05-25 Kailahun Kissi Tonge

4 4 15 F confirmed 2014-05-21 2014-05-26 Kailahun Kissi Teng

5 5 19 F confirmed 2014-05-21 2014-05-26 Kailahun Kissi Teng

6 6 55 F confirmed 2014-05-21 2014-05-26 Kailahun Kissi Teng

7 7 50 F confirmed 2014-05-21 2014-05-26 Kailahun Kissi Teng

8 8 8 F confirmed 2014-05-22 2014-05-27 Kailahun Kissi Teng

9 9 54 F confirmed 2014-05-22 2014-05-27 Kailahun Kissi Teng

10 10 57 F confirmed 2014-05-22 2014-05-27 Kailahun Kissi Teng

# ℹ 11,893 more rowsHow to rearrange my input data?

Rearranging the input data for data analysis can take most of the time. To get ready-to-analyse aggregated incidence data, we encourage you to use incidence2!

First, in the Get

started vignette from the incidence2 package, explore

how to use the date_index argument when reading a linelist

with dates in multiple column.

Then, refer to the cfr reference manual on Prepare

common epidemiological data formats for CFR estimation on how to use

the cfr::prepare_data() function from incidence2

objects.

R

# Load packages

library(cfr)

library(epiparameter)

library(incidence2)

library(outbreaks)

library(tidyverse)

# Access delay distribution

mers_delay <-

epiparameter::epiparameter_db(

disease = "mers",

epi_name = "onset to death",

single_epiparameter = TRUE

)

# Read linelist

mers_korea_2015$linelist %>%

as_tibble() %>%

select(starts_with("dt_"))

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 162 × 6

dt_onset dt_report dt_start_exp dt_end_exp dt_diag dt_death

<date> <date> <date> <date> <date> <date>

1 2015-05-11 2015-05-19 2015-04-18 2015-05-04 2015-05-20 NA

2 2015-05-18 2015-05-20 2015-05-15 2015-05-20 2015-05-20 NA

3 2015-05-20 2015-05-20 2015-05-16 2015-05-16 2015-05-21 2015-06-04

4 2015-05-25 2015-05-26 2015-05-16 2015-05-20 2015-05-26 NA

5 2015-05-25 2015-05-27 2015-05-17 2015-05-17 2015-05-26 NA

6 2015-05-24 2015-05-28 2015-05-15 2015-05-17 2015-05-28 2015-06-01

7 2015-05-21 2015-05-28 2015-05-16 2015-05-17 2015-05-28 NA

8 2015-05-26 2015-05-29 2015-05-15 2015-05-15 2015-05-29 NA

9 NA 2015-05-29 2015-05-15 2015-05-17 2015-05-29 NA

10 2015-05-21 2015-05-29 2015-05-16 2015-05-16 2015-05-29 NA

# ℹ 152 more rowsR

# Use {incidence2} to count daily incidence

mers_incidence <- mers_korea_2015$linelist %>%

# converto to incidence2 object

incidence(date_index = c("dt_onset", "dt_death")) %>%

# complete dates from first to last

incidence2::complete_dates()

# Inspect incidence2 output

mers_incidence

OUTPUT

# incidence: 72 x 3

# count vars: dt_death, dt_onset

date_index count_variable count

<date> <chr> <int>

1 2015-05-11 dt_death 0

2 2015-05-11 dt_onset 1

3 2015-05-12 dt_death 0

4 2015-05-12 dt_onset 0

5 2015-05-13 dt_death 0

6 2015-05-13 dt_onset 0

7 2015-05-14 dt_death 0

8 2015-05-14 dt_onset 0

9 2015-05-15 dt_death 0

10 2015-05-15 dt_onset 0

# ℹ 62 more rowsR

# Prepare data from {incidence2} to {cfr}

mers_incidence %>%

cfr::prepare_data(

cases_variable = "dt_onset",

deaths_variable = "dt_death"

)

OUTPUT

date deaths cases

1 2015-05-11 0 1

2 2015-05-12 0 0

3 2015-05-13 0 0

4 2015-05-14 0 0

5 2015-05-15 0 0

6 2015-05-16 0 0

7 2015-05-17 0 1

8 2015-05-18 0 1

9 2015-05-19 0 0

10 2015-05-20 0 5

11 2015-05-21 0 6

12 2015-05-22 0 2

13 2015-05-23 0 4

14 2015-05-24 0 2

15 2015-05-25 0 3

16 2015-05-26 0 1

17 2015-05-27 0 2

18 2015-05-28 0 1

19 2015-05-29 0 3

20 2015-05-30 0 5

21 2015-05-31 0 10

22 2015-06-01 2 16

23 2015-06-02 0 11

24 2015-06-03 1 7

25 2015-06-04 1 12

26 2015-06-05 1 9

27 2015-06-06 0 7

28 2015-06-07 0 7

29 2015-06-08 2 6

30 2015-06-09 0 1

31 2015-06-10 2 6

32 2015-06-11 1 3

33 2015-06-12 0 0

34 2015-06-13 0 2

35 2015-06-14 0 0

36 2015-06-15 0 1R

# Estimate delay-adjusted CFR

mers_incidence %>%

cfr::prepare_data(

cases_variable = "dt_onset",

deaths_variable = "dt_death"

) %>%

cfr::cfr_static(delay_density = function(x) density(mers_delay, x))

OUTPUT

severity_estimate severity_low severity_high

1 0.1377 0.0716 0.2288Severity heterogeneity

The CFR may differ across populations (e.g. age, space, treatment); quantifying these heterogeneities can help target resources appropriately and compare different care regimens (Cori et al., 2017).

Use the cfr::covid_data data frame to estimate a

delay-adjusted CFR stratified by country.

One way to do a stratified analysis is to apply a model to

nested data. This {tidyr}

vignette shows you how to apply the group_by() +

nest() to nest data, and then mutate() +

map() to apply the model.

R

library(cfr)

library(epiparameter)

library(tidyverse)

covid_data %>% glimpse()

OUTPUT

Rows: 20,786

Columns: 4

$ date <date> 2020-01-03, 2020-01-03, 2020-01-03, 2020-01-03, 2020-01-03, 2…

$ country <chr> "Argentina", "Brazil", "Colombia", "France", "Germany", "India…

$ cases <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

$ deaths <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…R

delay_onset_death <-

epiparameter::epiparameter_db(

disease = "covid",

epi_name = "onset to death",

single_epiparameter = TRUE

)

covid_data %>%

group_by(country) %>%

nest() %>%

mutate(

temp =

map(

.x = data,

.f = cfr::cfr_static,

delay_density = function(x) density(delay_onset_death, x)

)

) %>%

unnest(cols = temp)

OUTPUT

# A tibble: 19 × 5

# Groups: country [19]

country data severity_estimate severity_low severity_high

<chr> <list> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 Argentina <tibble> 0.0133 0.0133 0.0133

2 Brazil <tibble> 0.0195 0.0195 0.0195

3 Colombia <tibble> 0.0225 0.0224 0.0226

4 France <tibble> 0.0044 0.0044 0.0044

5 Germany <tibble> 0.0045 0.0045 0.0045

6 India <tibble> 0.0119 0.0119 0.0119

7 Indonesia <tibble> 0.024 0.0239 0.0241

8 Iran <tibble> 0.0191 0.0191 0.0192

9 Italy <tibble> 0.0075 0.0075 0.0075

10 Mexico <tibble> 0.0461 0.046 0.0462

11 Peru <tibble> 0.0502 0.0501 0.0504

12 Poland <tibble> 0.0186 0.0186 0.0187

13 Russia <tibble> 0.0182 0.0182 0.0182

14 South Africa <tibble> 0.0254 0.0253 0.0255

15 Spain <tibble> 0.0087 0.0087 0.0087

16 Turkey <tibble> 0.006 0.006 0.006

17 Ukraine <tibble> 0.0204 0.0203 0.0205

18 United Kingdom <tibble> 0.009 0.009 0.009

19 United States <tibble> 0.0111 0.0111 0.0111Great! Now you can use similar code for any other stratified analysis like age, regions or more!

But, how can we interpret that there is a country variability of severity from the same diagnosed pathogen?

Local factors like testing capacity, the case definition, and sampling regime can affect the report of cases and deaths, thus affecting case ascertainment. Take a look to the cfr vignette on Estimating the proportion of cases that are ascertained during an outbreak!

Appendix

The cfr package has a function called

cfr_time_varying() with functionality that differs from

cfr_rolling().

When to use cfr_rolling()?

cfr_rolling() shows the estimated CFR on each outbreak

day, given that future data on cases and deaths is unavailable at the

time. The final value of cfr_rolling() estimates is

identical to cfr_static() on the same data.

Remember, as shown above, cfr_rolling() is helpful to

get early-stage CFR estimates and check whether an outbreak’s CFR

estimate has stabilised. Thus, cfr_rolling() is not

sensitive to the length or size of the epidemic.

When to use

cfr_time_varying()?

On the other hand, cfr_time_varying() calculates the CFR

over a moving window and helps to understand changes in CFR due to

changes in the epidemic, e.g. due to a new variant or increased immunity

from vaccination.

However, cfr_time_varying() is sensitive to sampling

uncertainty. Thus, it is sensitive to the size of the outbreak. The

higher the number of cases with expected outcomes on a given day, the

more reasonable estimates of the time-varying CFR we will get.

For example, with 100 cases, the fatality risk estimate will, roughly

speaking, have a 95% confidence interval ±10% of the mean estimate

(binomial CI). So if we have >100 cases with expected outcomes on

a given day, we can get reasonable estimates of the time varying

CFR. But if we only have >100 cases over the course of the whole

epidemic, we probably need to rely on cfr_rolling()

that uses the cumulative data.

We invite you to read this vignette

about the cfr_time_varying() function.

Key Points

Use cfr to estimate severity

Use

cfr_static()to estimate the overall CFR with the latest data available.Use

cfr_rolling()to show what the estimated CFR would be on each day of the outbreak.Use the

delay_densityargument to adjust the CFR by the corresponding delay distribution.