Scenario modelling can guide epidemic response measures by helping to establish general principles around the potential effects of interventions, or

… how might things change if policies are brought in …

– UK Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies Epidemiological Modelling FAQ

Scenarios differ from true forecasts in projecting much farther ahead (typically months rather than days), and large-scale scenario modelling that includes both pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions was widely adopted during the Covid-19 pandemic and has been applied to endemic infections as well (Howerton et al. 2023; Prasad et al. 2023).

This vignettes shows how epidemics can be used to tun multiple scenarios of epidemic response measures, and include parameter uncertainty when running multiple scenarios.

New to modelling interventions using epidemics? It may help to read these vignettes first:

Code

epidemics model functions can accept lists of intervention sets and vaccination regimes, allowing multiple intervention, vaccination, and combined intervention-and-vaccination sets to be modelled on the same population.

Some benefits of passing lists of composable elements:

Combinations of intervention and vaccination scenarios can be conveniently created, as model functions will automatically create all possible combinations of the arguments to

interventionandvaccination;Input-checking and cross-checking is reduced by checking each element of the

interventionandvaccinationlist independently before the combination is created (and against thepopulation, for cross-checking); hence for \(N\) intervention sets and \(M\) vaccination regimes there are only \(N+M\) cross-checks, rather than \(N \times M\) cross-checks;Model output is organised to provide a scenario identifier, making subsetting easier (more on this below).

It may help to read the “Modelling a non-pharmaceutical intervention targeting social contacts” and the “Modelling the effect of a vaccination campaign” vignettes first!

Which model components can be passed as lists

epidemics currently offers the ability to pass intervention sets and vaccination regimes as lists.

It is not currently possible to pass lists of populations, seasonality, or population changes to any models.

In future, it may be possible to pass multiple populations as a list, to rapidly and conveniently model an epidemic on different populations, or to examine the effect of assumptions about the population’s social contacts or demographic structure.

Setting up the epidemic context

We model an influenza epidemic in the U.K. population while separating outcomes into three age groups, 0 – 19, 20 – 39, > 40, with social contacts stratified by age. Click on “Code” below to see the hidden code used to set up a population in this vignette. For more details on how to define populations and initial model conditions please see the “Getting started with epidemic scenario modelling components” vignette.

Code

# load contact and population data from socialmixr::polymod

polymod <- socialmixr::polymod

contact_data <- socialmixr::contact_matrix(

polymod,

countries = "United Kingdom",

age.limits = c(0, 20, 40),

symmetric = TRUE

)

# prepare contact matrix

contact_matrix <- t(contact_data$matrix)

# prepare the demography vector

demography_vector <- contact_data$demography$population

names(demography_vector) <- rownames(contact_matrix)

# initial conditions

initial_i <- 1e-6

initial_conditions <- c(

S = 1 - initial_i, E = 0, I = initial_i, R = 0, V = 0

)

# build for all age groups

initial_conditions <- rbind(

initial_conditions,

initial_conditions,

initial_conditions

)

# assign rownames for clarity

rownames(initial_conditions) <- rownames(contact_matrix)Code

# UK population created from hidden code

uk_population <- population(

name = "UK",

contact_matrix = contact_matrix,

demography_vector = demography_vector,

initial_conditions = initial_conditions

)Creating a list of intervention sets

We shall create a list of ‘intervention sets’, each set representing a scenario of epidemic response measures.

Note that each intervention set is simply a list of <intervention> objects; typically, a single <contacts_intervention> and any <rate_interventions> on infection parameters.

Code

max_time <- 600

# prepare durations as starting at 25% of the way through an epidemic

# and ending halfway through

time_begin <- max_time / 4

time_end <- max_time / 2

# create three distinct contact interventions

# prepare an intervention that models school closures for 180 days

close_schools <- intervention(

name = "School closure",

type = "contacts",

time_begin = time_begin,

time_end = time_end,

reduction = matrix(c(0.3, 0.01, 0.01))

)

# prepare an intervention which mostly affects adults 20 -- 65

close_workplaces <- intervention(

name = "Workplace closure",

type = "contacts",

time_begin = time_begin,

time_end = time_end,

reduction = matrix(c(0.01, 0.3, 0.01))

)

# prepare a combined intervention

combined_intervention <- c(close_schools, close_workplaces)Code

# create a mask-mandate rate intervention

# prepare an intervention that models mask mandates for 300 days

mask_mandate <- intervention(

name = "mask mandate",

type = "rate",

time_begin = time_begin,

time_end = time_end,

reduction = 0.1

)Having prepared the interventions, we create intervention sets, and pass them to a model function.

Code

# create intervention sets, which are combinations of contacts and rate

# interventions

intervention_scenarios <- list(

scenario_01 = list(

contacts = close_schools

),

scenario_02 = list(

contacts = close_workplaces

),

scenario_03 = list(

contacts = combined_intervention

),

scenario_04 = list(

transmission_rate = mask_mandate

),

scenario_05 = list(

contacts = close_schools,

transmission_rate = mask_mandate

),

scenario_06 = list(

contacts = close_workplaces,

transmission_rate = mask_mandate

),

scenario_07 = list(

contacts = combined_intervention,

transmission_rate = mask_mandate

)

)Note that there is no parameter uncertainty included here. We can visualise the effect of each intervention set in the form of the epidemic’s final size, aggregating over age groups.

The output is a nested <data.table> as before — we can quickly get a table of the final epidemic sizes for each scenarios — this is a key initial indicator of the effectiveness of interventions.

Note that in this example, we use the model’s default \(R\) estimate of 1.3. This is because at higher values of \(R\), we get counter-intuitive results for the effects of interventions that reduce transmission. This is explored in more detail later in this vignette.

Code

# pass the list of intervention sets to the model function

output <- model_default(

uk_population,

intervention = intervention_scenarios,

time_end = 600

)

# examine the output

head(output)

#> transmission_rate infectiousness_rate recovery_rate time_end param_set

#> <num> <num> <num> <num> <int>

#> 1: 0.1857143 0.5 0.1428571 600 1

#> 2: 0.1857143 0.5 0.1428571 600 1

#> 3: 0.1857143 0.5 0.1428571 600 1

#> 4: 0.1857143 0.5 0.1428571 600 1

#> 5: 0.1857143 0.5 0.1428571 600 1

#> 6: 0.1857143 0.5 0.1428571 600 1

#> population intervention vaccination time_dependence increment scenario

#> <list> <list> <list> <list> <num> <int>

#> 1: <population[4]> <list[1]> <list[1]> 1 1

#> 2: <population[4]> <list[1]> <list[1]> 1 2

#> 3: <population[4]> <list[1]> <list[1]> 1 3

#> 4: <population[4]> <list[1]> <list[1]> 1 4

#> 5: <population[4]> <list[2]> <list[1]> 1 5

#> 6: <population[4]> <list[2]> <list[1]> 1 6

#> data

#> <list>

#> 1: <data.table[9015x4]>

#> 2: <data.table[9015x4]>

#> 3: <data.table[9015x4]>

#> 4: <data.table[9015x4]>

#> 5: <data.table[9015x4]>

#> 6: <data.table[9015x4]>Output type for list intervention inputs

The output of model_*() when either intervention or vaccination is passed a list, is a nested <data.table>.

This is similar to the output type when parameters are passed as vectors, but with the "scenario" column indicating each intervention set as a distinct scenario, which helps with grouping the model outputs in "data".

The function epidemic_size() can be applied to the nested data column data to get the final size for each scenario.

Code

# set intervention labels

labels <- c(

"Close schools", "Close workplaces", "Close both",

"Mask mandate", "Masks + close schools", "Masks + close workplaces",

"Masks + close both"

)

epidemic_size_estimates <- mutate(

output,

scenario = labels,

size = scales::comma(

map_dbl(data, epidemic_size, by_group = FALSE, include_deaths = FALSE)

)

) %>%

select(scenario, size)

# view the final epidemic sizes

epidemic_size_estimates

#> scenario size

#> <char> <char>

#> 1: Close schools 21,495,236

#> 2: Close workplaces 22,423,830

#> 3: Close both 6,622,568

#> 4: Mask mandate 22,712,782

#> 5: Masks + close schools 17,215,645

#> 6: Masks + close workplaces 20,564,673

#> 7: Masks + close both 2,044,188This example shows how implementing interventions that reduce transmission can reduce the size of an epidemic.

Combinations of intervention and vaccination scenarios

When either or both intervention and vaccination are passed as lists (of intervention sets, or of vaccination regimes, respectively), the model is run for each combination of elements.

Thus for \(M\) intervention sets and \(N\) vaccination regimes, the model runs \(M \times N\) times, and each combination is treated as a unique scenario.

Note that ‘no intervention’ and ‘no vaccination’ scenarios are not automatically created, and must be passed explicitly as NULL in the respective lists.

While the number of intervention and vaccination combinations are not expected to be very many, the addition of parameter uncertainty for each scenario (next section) may rapidly multiply the number of times the model is run. Users are advised to be mindful of the number of scenario combinations they create.

The unnesting of the output follows the same procedure as before, and is not shown here.

Modelling epidemic response scenarios with parameter uncertainty

epidemics allows parameter uncertainty to be combined with scenario models of multiple intervention sets or vaccination campaigns.

Here, we shall draw 100 samples of the transmission rate with a mean of 0 and a low standard deviation of 0.005.

Code

# this example includes 100 samples of transmission rates for each intervention

# including the baseline

scenarios <- model_default(

uk_population,

transmission_rate = beta,

intervention = intervention_scenarios,

time_end = 600

)The output is a nested <data.table> as before, and can be handled in the same way.

Output type for intervention and parameter set combinations

The output of model_*() when either intervention or vaccination is passed a list, and when any of the infection parameters is passed as a vector is a nested <data.table>.

The "scenario" column indicates each intervention set as a distinct scenario, while the "param_set" column indicates the parameter set used for the model run.

The same parameters are used for each scenario, allowing for comparability between scenarios at the aggregate level.

The output has \(M \times N \times S\) rows (and nested model outputs), for \(M\) intervention sets, \(N\) vaccination regimes, and \(S\) infection parameter sets.

Comparing response scenarios with parameter uncertainty

When running multiple scenarios with parameter uncertainty, there may easily be hundreds of output rows corresponding to each scenario and parameter set combination. This can become challenging to handle and lead to comparisons that are not valid, such as across different parameter sets.

The outcomes_averted() function can help to quickly calculate the differences in epidemic sizes between a baseline scenario and any number of alternative or comparator scenarios.

The function ensures that alternative scenarios share the same characteristics, such as infection parameters, with the baseline scenario.

It also ensures like-for-like comparisons between scenarios and the baselines by matching output data from each scenario to its direct counterfactual in the baseline, ensuring that the only differences in outcomes are due to the implementation of interventions.

We re-use the transmission rate values drawn earlier to represent uncertainty in this parameter.

Code

# run a baseline scenario with no epidemic response against which to compare

# previously generated scenario data

baseline <- model_default(

uk_population,

transmission_rate = beta,

time_end = 600

)We use outcomes_averted() to calculate the total number of cases averted across all demographic groups for each parameter set.

Code

intervention_effect <- outcomes_averted(

baseline = baseline, scenarios = scenarios,

by_group = FALSE,

summarise = FALSE

)Code

# Plot distribution of differences

ggplot(

intervention_effect,

aes(x = outcomes_averted, y = factor(scenario), fill = factor(scenario))

) +

stat_histinterval(

normalize = "xy", breaks = 11,

show.legend = FALSE

) +

labs(

title = "Scenario comparison",

x = "Infections averted"

) +

scale_x_continuous(

labels = scales::comma

) +

scale_y_discrete(

name = NULL,

labels = labels

) +

scale_fill_discrete_qualitative(

palette = "Dynamic"

) +

theme_bw()

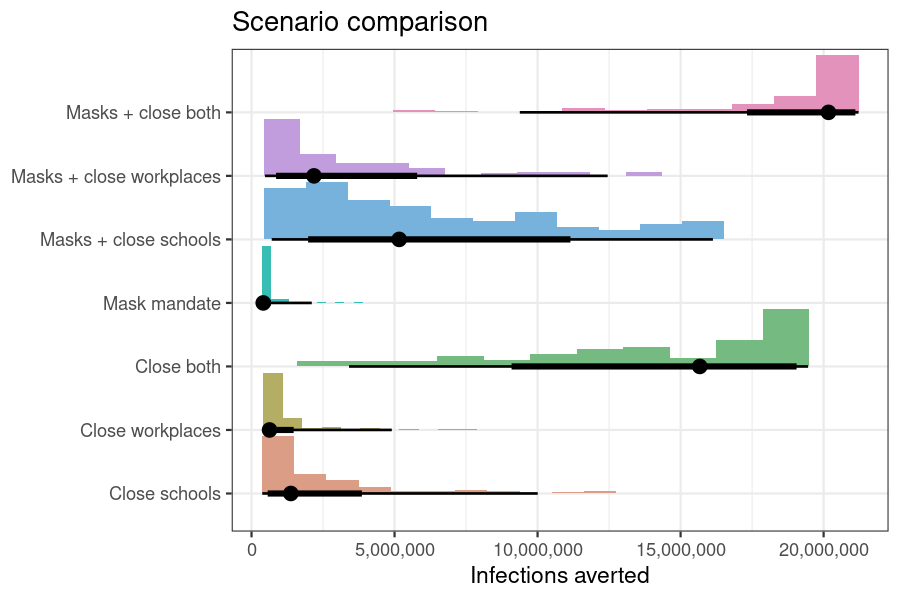

Figure 1: Infections averted relative to no epidemic response by implementing each scenario, while accounting with parameter uncertainty in the transmission rates.

We can get more compact data suitable for tables by summarising the output to get a summary of the median cases averted along with the 95% uncertainty interval using the summarise argument, and we can also disaggregate the cases averted by demographic group using the by_group argument. Both these options are TRUE by default.

Code

outcomes_averted(

baseline = baseline, scenarios = scenarios

)

#> scenario demography_group averted_median averted_lower averted_upper

#> <int> <char> <num> <num> <num>

#> 1: 1 40+ 589048.1 146305.71 4009551.3

#> 2: 1 [0,20) 385913.2 127262.58 3050479.1

#> 3: 1 [20,40) 399297.9 98807.37 2944726.6

#> 4: 2 40+ 262316.9 168090.68 2009812.7

#> 5: 2 [0,20) 159312.2 94876.04 1445639.4

#> 6: 2 [20,40) 204989.2 146947.05 1448337.6

#> 7: 3 40+ 6353711.9 1495432.76 7625962.3

#> 8: 3 [0,20) 4707535.8 914359.58 6140493.0

#> 9: 3 [20,40) 4609764.7 998536.62 5722732.9

#> 10: 4 40+ 177696.7 151511.91 875323.8

#> 11: 4 [0,20) 112334.1 96648.67 610919.2

#> 12: 4 [20,40) 118987.6 102234.53 619858.6

#> 13: 5 40+ 2192652.7 308110.77 6268222.9

#> 14: 5 [0,20) 1455851.1 196195.46 5117644.8

#> 15: 5 [20,40) 1514102.3 202017.32 4744802.5

#> 16: 6 40+ 940071.4 200491.93 4941637.8

#> 17: 6 [0,20) 597879.3 115470.48 3841185.9

#> 18: 6 [20,40) 645238.7 156166.52 3667693.2

#> 19: 7 40+ 8036211.5 4007084.99 8359423.7

#> 20: 7 [0,20) 6256733.1 2621049.09 6639901.1

#> 21: 7 [20,40) 5930346.6 2750447.81 6239290.9

#> scenario demography_group averted_median averted_lower averted_upperCounter-intuitive effects of time-limited interventions

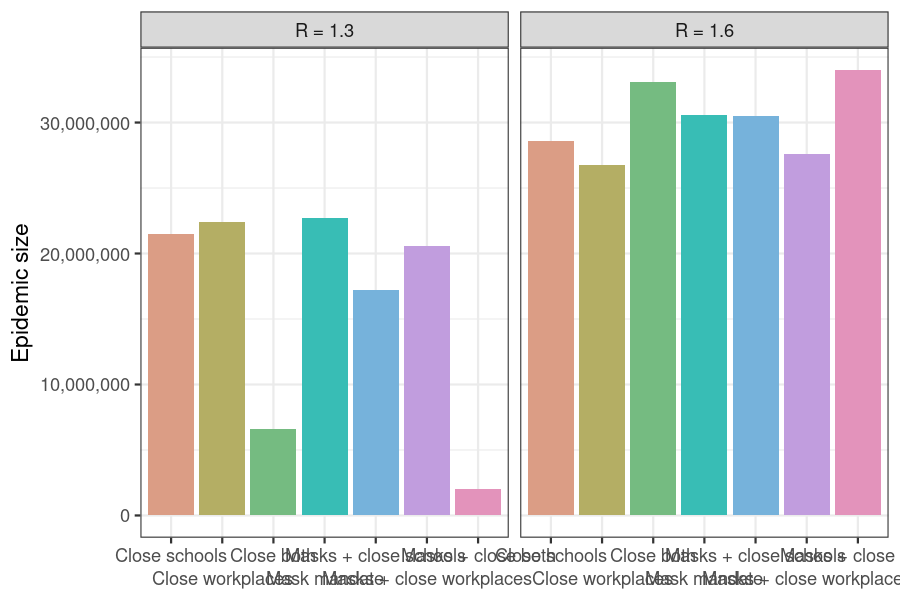

The intervention scenarios modelled above suggest that:

interventions on disease transmission rates reduce infections and hence epidemic final sizes;

multiple interventions reduce epidemic final sizes more than single interventions.

In this simple example we show how this need not always be the case, and that counter-intuitively, implementing more interventions can lead to a larger epidemic final size than implementing fewer interventions.

This phenomenon depends on the baseline transmission rate of the infection, so we select a relatively low \(R\) of 1.30 (corresponding to pandemic influenza), and a higher \(R\) of 1.6 to illustrate the point.

Code

# run each scenario for two values of R

# no parameter uncertainty

r_values <- c(1.3, 1.6)

output <- model_default(

uk_population,

transmission_rate = r_values / 7,

intervention = intervention_scenarios,

time_end = 600

)

# obtain epidemic sizes

epidemic_size_estimates <- mutate(

output,

size = map_dbl(

data, epidemic_size,

by_group = FALSE, include_deaths = FALSE

),

r_value = rep(r_values, each = length(intervention_scenarios)),

scenario = rep(factor(labels, labels), 2)

) %>%

select(r_value, scenario, size)Code

# plot the epidemic final size for each scenario for each R

ggplot(epidemic_size_estimates) +

geom_col(

aes(scenario, size, fill = scenario),

show.legend = FALSE

) +

scale_x_discrete(

name = NULL,

guide = guide_axis(n.dodge = 2)

) +

scale_y_continuous(

labels = scales::comma,

name = "Epidemic size"

) +

scale_fill_discrete_qualitative(

palette = "Dynamic"

) +

facet_grid(

cols = vars(r_value),

labeller = labeller(

r_value = function(x) sprintf("R = %s", x)

)

) +

theme_bw()

Figure 2: Counter-intuitive effects of time-limited interventions on transmission rate at high R values. Scenarios in which multiple interventions are implemented may have a larger final epidemic size than scenarios with fewer interventions, e.g. the ‘Close both workplaces and schools’ scenario.

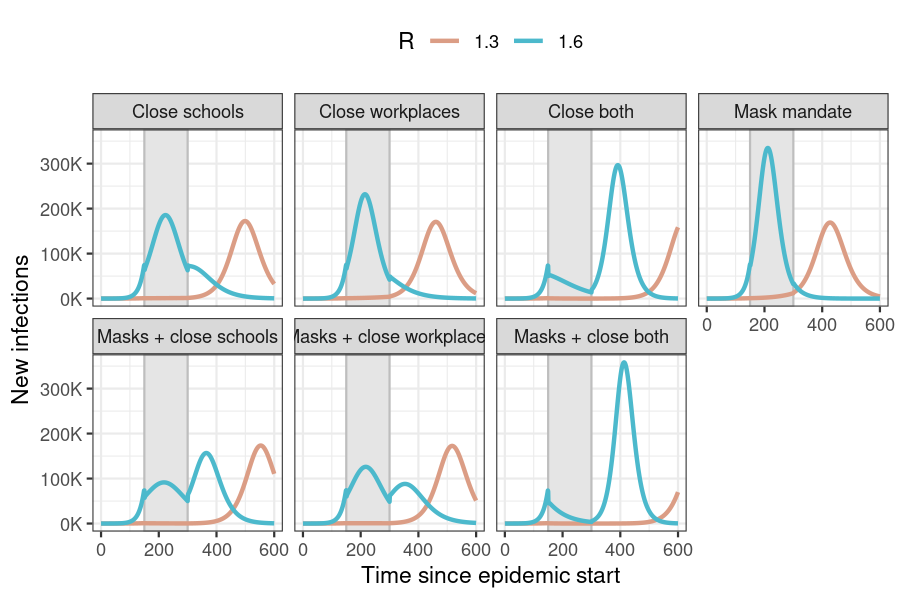

Plotting the epidemic trajectories for each scenario for each value of \(R\) gives a fuller picture of why we see this unexpected effect.

Code

# get new infections per day

daily_incidence <- mutate(

output,

r_value = rep(r_values, each = length(intervention_scenarios)),

scenario = rep(factor(labels, labels), 2),

incidence_data = map(data, new_infections, by_group = FALSE)

) %>%

select(scenario, r_value, incidence_data) %>%

unnest(incidence_data)Code

ggplot(daily_incidence) +

annotate(

geom = "rect",

xmin = time_begin, xmax = time_end,

ymin = -Inf, ymax = Inf,

fill = "grey90", colour = "grey"

) +

geom_line(

aes(time, new_infections, col = as.factor(r_value)),

show.legend = TRUE, linewidth = 1

) +

scale_y_continuous(

labels = scales::label_comma(scale = 1e-3, suffix = "K")

) +

scale_colour_discrete_qualitative(

palette = "Dynamic",

name = "R"

) +

facet_wrap(facets = vars(scenario), nrow = 2) +

theme_bw() +

theme(legend.position = "top") +

labs(

x = "Time since epidemic start",

y = "New infections"

)

Figure 3: New daily infections in each intervention scenario for two values of R. The period in which interventions are active is shown by the area shaded in grey. No interventions are active in the ‘No response’ scenario.

Implementing interventions on the disease transmission rate leads to a ‘flattening of the curve’ (reduced daily incidence in comparison with no response) while the interventions are active.

However, these cases are deferred rather than prevented entirely, and in both scenarios this is seen as a shifting of the incidence curve to the right (towards the end of the simulation period).

When \(R\) is low, the incidence curve begins to rise later than when \(R\) is high (interventions applied to these epidemics actually miss the projected peak of the epidemic, but still shift cases to the right). Thus low \(R\) epidemics do not run their course by the time the simulation ends, making is appear as though interventions have succeeded in averting infections.

At higher \(R\), the peak of the projected incidence curve without interventions falls within the intervention period, and thus all interventions reduce new infections. In scenarios with multiple active interventions, a large number of susceptibles remain uninfected, compared to scenarios with fewer interventions. The former thus see higher incidence peaks, leading to counter-intuitively larger final epidemic sizes.